Killing Our Gods: A Game Beyond the Endgame—On Anodyne 2, Judgement, and Revolution

Killing Our Gods is a monthly column from Grace Benfell about Christianity, religion, and role-playing through a queer, Marxist, and lapsed Mormon lens.

This essay contains spoilers for Cloud Atlas, The Lathe of Heaven, and Anodyne 2: Return to Dust

Close to the end of his revelation, John witnesses “a new heaven and a new earth.” He sees “a holy city… coming out of heaven from God.” In this city, God will dwell among the people and “Death will be no more; mourning and crying and pain will be no more, for the first things have passed away.” The first things, in this case, means the old ways of the world. Every living thing has known death and sickness and struggle. That will, on some unimaginable day, end. It has often been observed, but Marxist promise of the day of revolution is remarkably similar. Marx paints the revolution as almost inevitable. Just as Feudalism ended, Capitalism will end. Its contradictions and the will of the people must ensure its downfall. Both promise, whether through the plan of the divine or the effort of revolutionaries, that everything will change. Sorrow as we know it will end.

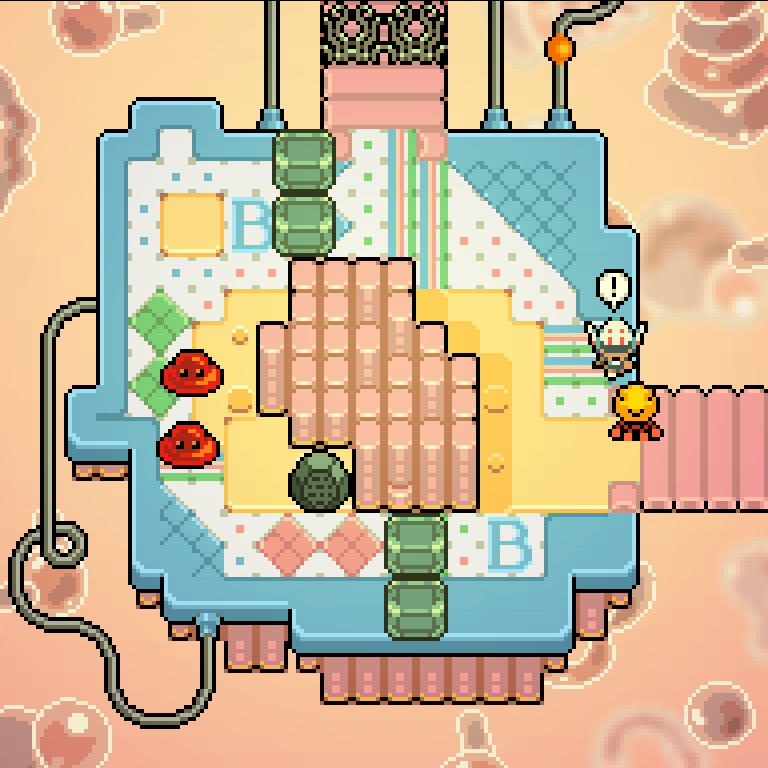

From her birth, Anodyne 2’s Nova is promised a new day. She is a Nano Cleaner, tasked by The Center to remove corrupting dust from its domain, New Theland. The dust, The Center claims, is the source of New Theland’s woes. Once Nova gathers and contains the dust, The Center can usher in The Anodyne, an era of peace for all The Center’s creations. The “game” of Anodyne 2 is thus entering the minds of New Theland’s various denizens, cleaning them of corruption, and then giving the dust back to The Center to fuel its world-spanning change.

What The Center promises quickly comes into conflict with what Nova sees. As she removes dust from New Cenote, New Theland’s metropolis, she finds that removing it can alleviate discomfort, but does not change the citizens’ often brutal circumstances.

An old woman languishes in her completed lamp shade collection. You can hear her coughs from outside her home. She claims the dust is to blame. Though Nova cures her of her illness by removing the dust, the woman remains alone as the dark of her home swallows her unseen possessions. In the back alleys, Nova finds a family of worms, ignored by the rest of the city and playing in the mud. Again her cure brings them temporary comfort, but does not give them a new home or a new place in the community. Instead she leaves them behind. The alleyways hide them.

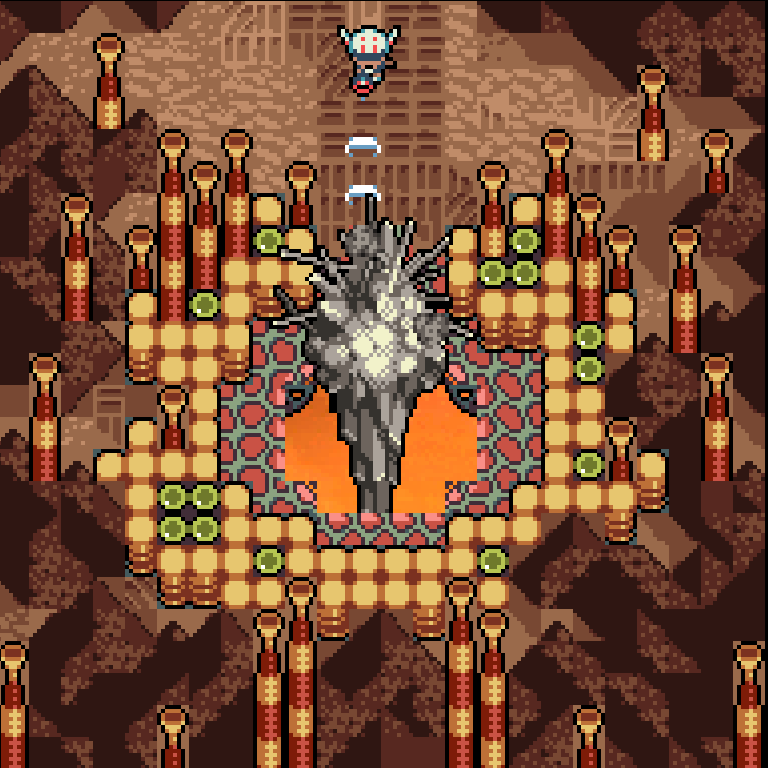

One of the most striking things about Anodyne 2 is how seriously it takes its absurdity. A lampshade collection is a silly image. On the walls of New Cenote’s alleyways, you will find graffiti reading “Environmental Storytelling.” However, the game also makes clear that these are real people with real struggles. For example, Nova initially soothes an angry monster wrecking a construction site, but later that monster reveals that his anger came from observing the inequality of the world. The mother worm rediscovers that she was made by The Center to “investigate the future by studying the gambling habits of birds.” Her newfound purpose though does not change her state, only placates her. The more people Nova cleans, the more potent the sense that Nova’s work does not resolve conflict, rather it smoothes it out. Cleaning dust is a placebo that does not address the source of pain, and perhaps does not even numb it.

The Center promises the end of suffering, but it is hollow and false. It says that a better world can be won through empty work and a flipped switch. As Austin Jones points out, The Center’s vision of work and life is complete and restless automation. Nova does need to eat, sleep, or drink. When Nova’s surrogate mother, Palisade, assures her daughter that “there is room in the world for all of Nova,” The Center erases her. A glandilock seed rests in Nova’s body which effectively acts as the cop in her head. It is quiet as Nova works, but rages when she deviates from the Center’s plan. Nova is, ideally, the frictionless tool of a master hand. She is a child of The Center in name, yes, but in practice her only value is work and obedience. In a sense, her role reflects the lies told by many christian communities. If we live unobtrusively and “kindly,” heaven will one day be before us.

Fittingingly, even the parts of The Center that gesture at utopia reinforce hegemonic violence. Representatives of The Center emphasize the decentering of the self and unity between all of The Center’s creations. The Anodyne promises to bring peace to the entire world. In practice, that peace is nothing but a freezing of existence. In one of the game’s two endings, Nova achieves the Anodyne. In the moment before it arrives, the camera cuts between many of the characters Nova has encountered. All wonder what the Anodyne will be, before a white light envelopes them. We are left with Nova and the two representatives of The Center frozen in plaster. Peace with no movement; the order preserved.

This echoes another false utopia, the world of Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Lathe of Heaven. In this science fiction novel, George Orr can alter reality by dreaming. He sees a therapist, Dr. William Haber, for help with this. Haber, rather than helping his patient, begins to put George into a sleep trance, allowing him to exploit George’s dream ability. At first he makes easy changes for George’s life, like a summer home or a simpler commute. Eventually, though, Dr. Haber uses this ability to stretch the world to his will.

The full implications of this are explored in the novel, but I want to zoom in on one aspect that reflects the Center’s insidious approach to unity. Dr. Haber asks George to dream of a world without racial conflict. Through the machinations of the subconscious, this wish becomes the total elimination of racial difference. Everyone is colored gray. As Dr. Haber puts it “there has never been a racial problem.” In the process, Heather, a biracial lawyer consulting George is erased from existence. George contemplates this, “She could not have been born grey… her anger, timidity, brashness, gentleness, all were elements of mixed being.” William’s elimination of difference also eliminated those affected by that difference.

Le Guin is not suggesting that racism is an inevitable fact of human life. Rather, her novel claims something must be done. We cannot simply erase race and wash our hands of the matter. We must reckon with the blood and the wrong done, with the lives and cultures created through survival. This takes work, and we cannot wait for the world to just get wise, we must act. Action is the opposite of both Dr. Haber and The Center’s approach to these questions. Though Anodyne 2 does not explicitly deal with race, The Center’s desire for total frictionless control reflects the white heaven of many Christians. From the benign seeming “racial difference won’t exist” to the flat hatred of “everyone will be white,” a false heaven can resemble both the sterileness of The Center and the battleship grey faces of The Lathe of Heaven. As the work of Kishonna Gray and Lisa Nakamura illustrates, the assumption of sameness, of a post racial world, institutes whiteness and oppression.

Anodyne 2 does offer an alternate means of addressing difference, rather than pledging cold unity. There is the small community of the Dustbound. When Palisade dies, she leaves Nova with a vision of a sanctuary she constructed for her. In the process of finding this vision, Nova stumbles across the Dustbound village. Rather than the cold metallic lines of The Center, the village’s colors are deep, earthy, and glitched out. The routine of finding dust fades away as the Dustbound take in Nova. Weeks and months pass. Anodyne 2 implies that the game proper is effectively in “real time.” The Center sustains Nova, so she can work without rest. In the village, the game has real cuts across time and space. This floaty abstract time connects the “work” of playing the game and the ineffectiveness of Nova’s task directly to The Center itself. The parts where Anodyne 2 is at its most video gamey are when Nova is working for The Center. The parts when narrative is more thoroughly mixed with play is when Nova begins to move away from The Center. In these moments, the game has the feeling of life lived, and not simply of work completed.

To be clear, Nora does work and does play in the Dustbound Village. She helps Elegy Beatty tend her gardens. She wrestles with her friend Drem, in some of the warmest feeling and collaborative moments in the game. However, these actions move toward sustaining and making joyful a community of many. Although Nova attempts to ignore it, this is her first moment of defying The Center. Of course, this comes with tension. Nova pours herself into the play place made by Palisade, mistaking it for a ritual ground. Every time her friends Elegy or Drem question The Center, the Glandilock seed screams in protest. Eventually the cognitive dissonance is too much for her and she leaves, throwing herself back into her work as the Nano Cleaner.

Nova’s ache is painfully recognizable. I too thought that following the rules would lead to the healing of pain, the restitution of myself. While sometimes, I felt enveloped in love of a community of Christians, I would also feel terribly, horribly alone. It was a pain so deep that I could barely recognize it. When I moved away from the rules, it would often just expose pain rather than alleviate it. The promise of a day where things would be made right felt further and further away.

If you are like me, you will think often of the Dustbound as you complete more of Nova’s tasks. As she finds more broken, isolated souls, and weaves them closer to The Center instead of each other, you will think back to a village where a different way of being was shown. Upon her return though, she finds the village completely changed. The sterile lines of The Center have invaded this once free space. Drem does not remember her and spouts The Center’s propaganda. She encounters Elegy, unaffected through sheer luck, who encourages to follow her heart and free herself and others. Ultimately, Nova must choose between completing her mission or confronting The Center. From this choice comes the game’s two endings.

Nova’s ultimate decision reflects what James Baldwin calls “cosmic vengeance, based on the law that recognize when we say ‘whatever comes goes up, must come down.'” In his long essay “The Fire Next Time,” Baldwin draws a stark picture of the urgency with which the United States must address white supremacy. A day of change will come, the only question is what shape it will take. The title alludes to this. The punishment that will hit the world given voice through an old slave song. The question for Baldwin, and for human beings in the 21st Century I would argue, is not whether the day of judgement will come, but when and how.

As a reflection of this concept, both of Anodyne 2’s endings offer up a distinctly new state of the world. One offers sterility, the other life. One requires placidity, the other sacrifice. The first, already described, resembles the endgame of capitalism and white supremacy. Inequality and hurt will be maintained until the world ends. The other ending burns with furious hope. With the energy granted by the knowledge that, as Baldwin says, “Everything now… is in our hands; we have no right to assume otherwise,” Nova frees another Nano Cleaner from the influence of the Glandilock seed and with the help of her friends, vanquishes The Center’s power.

Nova’s actions echo a heroine in another world, Sonmi-451 from Cloud Atlas. Sonmi is a replicant, essentially a flesh and blood robot, freed by a resistance movement in a future Korea. Upon discovering the extent of the replicant’s exploitation, as well as the fact that they are fed, with some intermediate steps, the corpses of other replicants, Sonmi helps stage a bold revolution against the system and writes a manifesto for freedom. Ultimately though, she is captured. The text of her section of the novel is a transcript of her final interview before her execution. In it, she reveals that her entire existence has been a plot to turn the citizen population against replicants, an example of the system incorporating revolutionary impulses into itself. When the interviewer expresses bewilderment at Sonmi’s cooperation, she replies, “We see a game beyond the endgame. I refer to my Declarations… Every schoolchild… knows my twelve “blasphemies” now…My ideas have been reproduced a billionfold.” Sonmi’s bet is that her ideas will eventually rattle the system in a way that it cannot incorporate or anticipate.

While Nova “succeeds” where Sonmi “fails,” their actions show belief in something beyond the limits of the system. “The game beyond the endgame” feels especially pointed in comparison with Anodyne 2, because it, among everything else, attempts to imagine play separate from capitalism. Both Nova and Sonmi choose to believe that their life stretches out, that it can remake the world, and bear the blessed burden of life in their sacrifice. Whether that life shows itself in their continued existence or in the continuing existence of their words. To put it differently, they believe in the inevitability of revolution and their ability to shape its result.

Lotus observes in their analysis of Anodyne 2 that “what rings true about Nova’s predicament is that there is explicitly no distinction between the personal and political.” The story of Nova’s liberation is also the story of a community’s freedom. This observation rings across all the works cited here. Somni’s story has resonance for anyone becoming aware of atrocity and choosing to act even when action is compromised. George Orr’s dreams resemble our ability to shape the world with our thoughts. James Baldwin directly appeals to our, as in yours and my, power in The Fire Next Time. The future day of revolution has to happen now, in our hearts.

At the end of The Lathe of Heaven, the world has been freed from Dr. Haber’s influence, but in the process, all of George’s dreams have melded together, creating a world that feels strange and illogical. However, with that brokenness comes truth, Heather returns to life, and thus the tensions of contradictions of the world must be addressed. Similarly, the parts of Anodyne 2 that feel most alive are glitchy and fractured. Cloud Atlas, The Fire Next Time, and Anodyne 2 all point to the brokenness of the world. All still ask us to lean into that brokenness, to reach out our hands into the dust and dirt, to make something kinder and better on our own, collective, terms. The description of the judgement in John’s revelation echoes both The Center’s sterility and Nova’s eventual freedom. In some form, I suppose, I believe that John’s city will exist. But what it will be, what it will be made of, is up to no one but us.

1 thought on “Killing Our Gods: A Game Beyond the Endgame—On Anodyne 2, Judgement, and Revolution”