HIGH FIVE, KILL GOD: In Defense of the Power of Friendship

How many of our most profound memories were made in a McDonald’s parking lot?

We hunker motionless under the streetlights, hands stuffed with lukewarm French fries, asses damp from prolonged exposure to British weather. Music splutters from the speaker of an iPhone, its screen blurred by raindrops and finger grease. We speak in what ifs and remember whens. The food sucks, but that’s okay: we have the company of our friends, if only for a moment. We try to ignore the cold and the dark, none of us wanting to be the one to break us off back down to Earth.

“…I should probably go home.”

“Yeah, me too.”

* * *

When did we turn our backs on friendship? Do our teenage years leave us so humiliated that we gag-reflexively shut down any opportunity to take a second shot at high school, and the relationships that come with it? In this time of ever-growing hopelessness and government indifference, the appeal of the coming-of-age genre, with its raw sincerity and furious punk aesthetic, should be higher than ever. Yet in its rightful media abundance, we have lost all interest. The power of friendship as a narrative theme is “cringe” now, and no games draw more ire from fans than those beacons of adolescent embarrassment, Japanese RPGs.

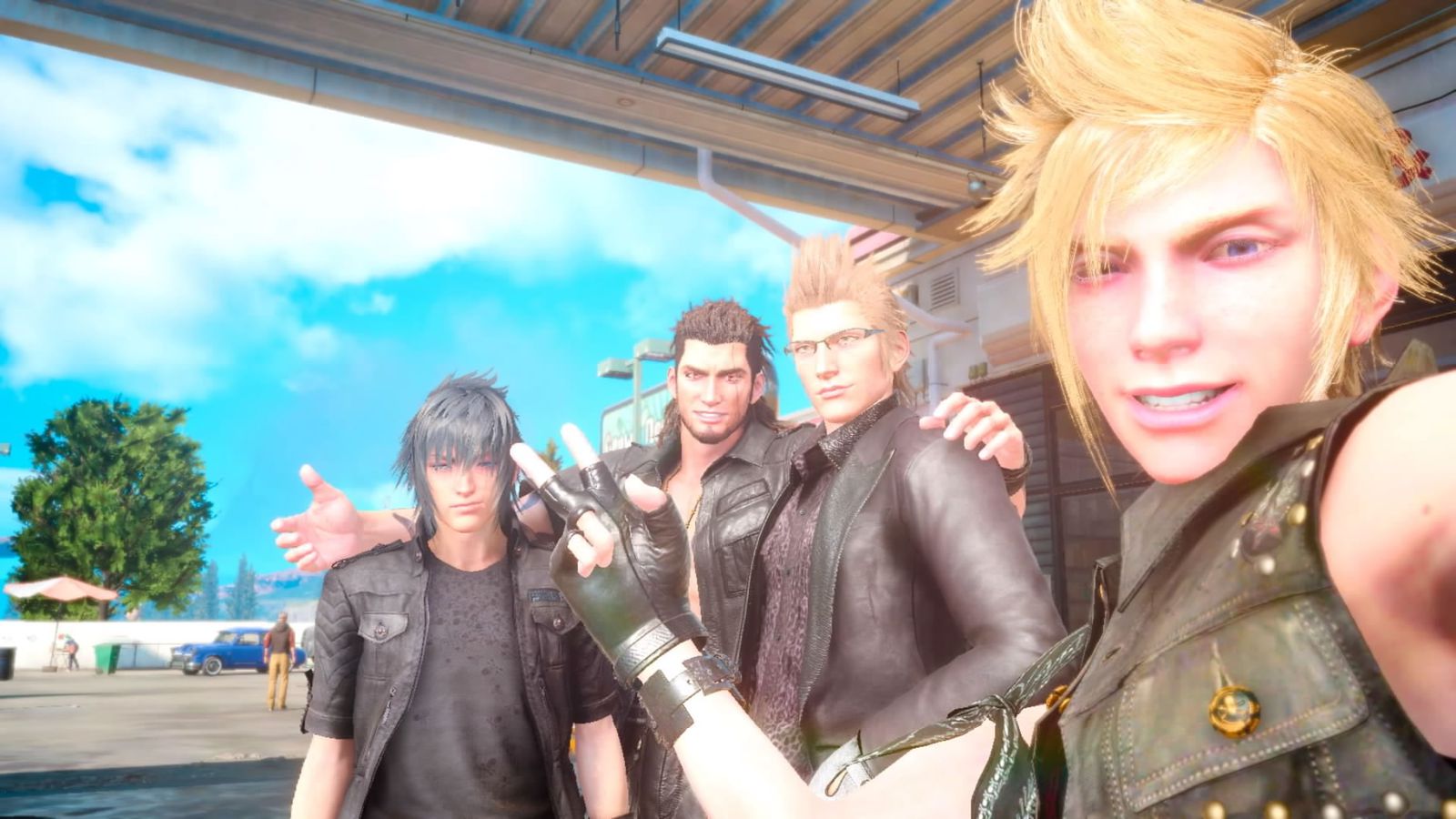

We roll our eyes at their trailers; we laugh at their every repeated battle joke. We brand their teenage outbursts clumsy, conveniently forgetting all the times we’ve responded to “enjoy your food” with “you too”. We as Gamers™ have collectively decided that we are “over” JRPGs and their childish sentimentality, preferring instead to chase the smoke-and-mirror highs of filmic storytelling. We don’t want quiet, oversharing companionship by the fire; we want loud, expensive games with all-American hero dads who will open any slightly-too-heavy door to save their families.

Take, for instance, the reflexively reviled opening of the otherwise beloved Kingdom Hearts II. Where other games front-load themselves with action setpieces, KHII instead makes a quite bargain with the player: it knows full well our desire to get back into hero Sora’s clown shoes and run around Disney worlds, yet still it traps us in an urban purgatory devoid of any such spectacle. Marooned with angsty new lead Roxas, we spend a seemingly interminable week in this so-called Twilight Town, wandering its ghostly streets, playing abysmal minigames for peanut prizes, loitering with our unrecognisable friends on clock towers and in alleyways. The days stretch out to infinity (“and beyond!”), yet by the end of the prologue it’s impossible not to feel connected to this gang on some level – we’ve delivered too many letters and eaten too many sea salt ice lollies together to pretend otherwise.

As a tween, I too laughed at JRPGS for their awkward honesty, running to whatever new movie game was out in an attempt to convince myself that “games are art, MOM.” As a high-schooler perched on the edge of adulthood and acutely aware that some of my friendships are on an invisible timer, nothing hurts more.

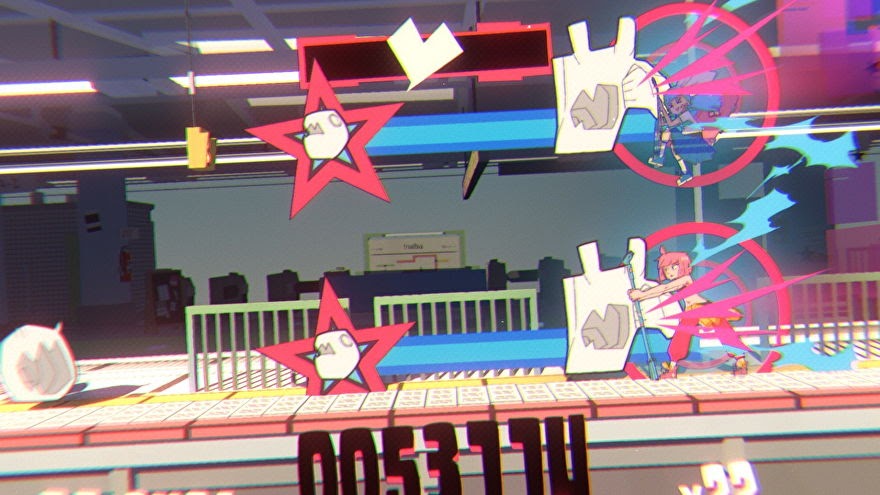

Fortunately for all but the most pithy of haters, friendship-as-narrative isn’t going anywhere. In their designers’ eternal commitment to using combat as a core mechanic, companionship – whether in its presence or absence – is fundamentally baked into the games we play: The World Ends With You asks you to constantly communicate with your partner in much the same way that a dancer might, while MMOs like Final Fantasy XIV force players to rely on one another to survive its toughest challenges. Revolving combat around a single character versus a team of unique helpers with their own quirks to balance can also hugely impact a game’s tone, be it solitary or supportive. Spider-Man’s god-awful one-liners just don’t feel right when he doesn’t have a boyband of anime characters to trade barbs and rip finishers with. Imagine if your chess pieces high-fived each other every turn. That’s Persona, dude.

Of course, the idea of developing relationships through casually inflicting suffering on others is often just as stereotypically macho as it sounds. For all my evangelising their infinite depth and symbol-laden design, JRPGs do seem far more interested in making it fun to hit things with a stick, and this emotional connection may well just be a side effect from decades of developers trying to appeal exclusively to an audience of boys and men. Dragon Quest teaches us that it feels good to grind sentient cucumbers into paste, and even better when our man-bros are egging us on. Yet if this really is such a great way to improve our bonds and be more open with one another rather than just a sweaty, not-gay-I-promise pissing contest, why do action games only ever seem to focus on men? Instead, the true power of these games is something altogether more nebulous than their moment-to-moment action, something bound neither by gender norms nor genre expectations: their inevitable end.

At the heart of teenage friendship lies something deeper than high fives and team-up attacks: the fraught sense of intimacy; the lingering fear of loss; the inevitable separation. There are people in all of our lives with whom we were once close but have now drifted away, and just as video games are able to strengthen character relationships through their interactivity, they can just as powerfully convey the exact opposite.

Killing whatever false deity is about to destroy (sorry, re-make) the universe at the end of a hundred-hour adventure isn’t what makes a final boss special. What truly matters is that it’s the last thing we as friends will get to do together, and that we may well never see each other again. Video games are unique in that they just can’t end without our input, and as such it is us who must make the ultimate decision to move on, to go home, to say goodbye. Sometimes, we are given a warning: a character will take us aside and tell us in no uncertain terms that this is it, there’s nothing left after this. We are offered one last chance to go see the world with our best friends, to spend as much time as we need together before that final encounter. We, of course, take it.

My bringing up McDonald’s doesn’t make it some exclusive temple of realisation, either (shout-out to all the Greggs fans reading this). Just as nobody wants to abandon their friends in the real world, we too shirk our responsibilities for the sake of spending a little longer in this virtual limbo, whatever and wherever it may be. We find ourselves hyper-focused on menial episodes of our lives, filling out fetch quests in the same way we might reminisce about a long lost classmate. We pretend we can stay here forever, knowing full well we can’t. Hanging out on borrowed time is an overpowering feeling, and one unique to the video game medium: more than in its cliché villains and puddle-deep ruminations on social media, Persona 5‘s half-sequel, half-epilogue Strikers finds true meaning in its almost apocalyptic sense of dread, its characters voicing greater and greater melancholy as their summer road trip steadily creeps to its end. The game closes with a joyous sky shot and a cry of “Until next time, phantom thieves!” but one question still remains: just how many next times will there be?

So what can we learn from our friends? More than anything, it’s that it wouldn’t hurt for games to touch the ground a little more often.: Why should we care about the biker bro struggles of Deacon St. John (that’s the guy from Far Cry, right?) when there are literally 400 hours worth of impossibly unimportant, immediately entertaining Love Island episodes, whose procedural, maze-like webs of hilariously identical relationships practically breed infectious outrage?

Kingdom Hearts II ‘s opening is powerful, not because it lets us play at being invincible heroes but because we can so easily see ourselves in its nobodies: to us, Roxas’ visions of black coats and white ghosts could just as easily be a new job, or a hurtful love affair, or whatever causes us to slowly part ways. A truly relatable story isn’t high-risk, nor is it high-reward (if there’s even a reward at all). It’s personal, and it’s tiny. It’s a Tomodachi Life group stage performance. It’s a tough mountain climb in Breath of the Wild. It’s meeting a brand new weirdo on the surrealist streets of Yakuza’s Kamurocho. It’s the entirety of Kind Words. It’s a late night McDonald’s meal in an empty car park, surrounded by the people we love most.

Our lives are not movies. They could never be a series of prescient events, divided neatly into story acts and character arcs, bound by everlasting friendships. We babble unscripted, trying desperately to appear clever, but exposing ourselves as anything but. Video games can be pretty stupid, too. JRPGs are both idiotic and powerful, often at the same time, and there’s a life-like beauty in that. Killing Evil Anime Jesus can wait. Holding our friends close can’t.

* * *

two boys sit by the shore

staring out into the moonlight

the sea is an inky black but

they don’t seem to mind.

“I wish I could live life the way you do. Just following my heart.”

“Yeah, well, I’ve got my fair share of problems too.”

“Like what?”

“Like… wanting to be like you.”

“Well, there is one advantage to being me… Something you could never imitate.”

“Really? What’s that?”

“Having you for a friend.”

“Then I guess… I’m okay the way I am. I’ve got something you could never imitate too.”