Provided by author

Games in Our Absence

Most games operate according to the observer effect — in the act of looking in, we inherently disturb the “dormant” facets of a game’s world. The universe changes due to the presence of its player, and only exists when we take its measure.

However, a handful of games function even without our influence, taking on a somewhat quantum state. Millennials who owned a Tamagotchi pet learned this the hard way, for example; the pet still gets hungry even when the tiny handheld is turned off. Most often, these types of domestic games are the ones that respond the most to our absence. Your lawn isn’t going to mow itself.

Animal Crossing is no exception — when we abandon our homes and return after many years, life has moved on. Wilting flowers and weeds cover the ground; we no longer recognize our neighbors, as new ones have moved in. The fish still swim up and downstream each season. The apples, cherries, oranges, and peaches you brought home from friends-of-friends have long since fallen from the withering trees.

Games come alive when we strike down enemies, open chests, and navigate to the next quest marker. In titles like Assassin’s Creed or The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, the world itself is hidden until we traverse more of it; the map appears before us only when we take those first steps into unseen territory. A player must play for any meaningful changes in the world to occur. But in Animal Crossing, the game continues on when we aren’t looking. The absence of player input does not halt any of its cognitive functions — it still calculates when the Summer Shells can be found, and which fruits will grow in three-day increments. The game, without us, will continue dreaming up the mechanics of decay.

And yet, there’s a comfort in games that have a life of their own, too. Sometimes it’s nice to imagine that the game makes itself hospitable to your virtual neighbors — their lives aren’t snuffed out when you’re too busy to play. They still experience good days, bad days, nights, rainstorms, and meteor showers. The stars fall even when we aren’t there to see them.

The vibrant, lively world of Undertale hides its own form of quantum uncertainty. It is neither a happy nor terrible place until we arrive to witness it; it exists on its own in a theoretical status quo without player intervention. Snowmen roll each other to life, popular TV broadcasts air from the local underground volcano, and children wonder about the stars they’ve never seen on the surface. We soon learn the history of this world, and the events leading up to our arrival — it simply is, continuing to function beyond our knowledge.

As soon as we step in, however, a shift occurs. Undertale suddenly exists at the mercy of its onlookers; the player is, in fact, an inter-dimensional presence with the ability to influence the game world in profound ways. While most characters are unaware of your existence, the select few that do know interact with the player in ways rarely seen in games. It is ultimately up to us whether or not a “happily ever after” can be achieved. We can murder everyone in the Underground without mercy, consigning the world to total death and silence that persists after we finish playing — or we can save the people of the Underground and resolve a centuries-long crisis that trapped them below the surface, letting everyone go free.

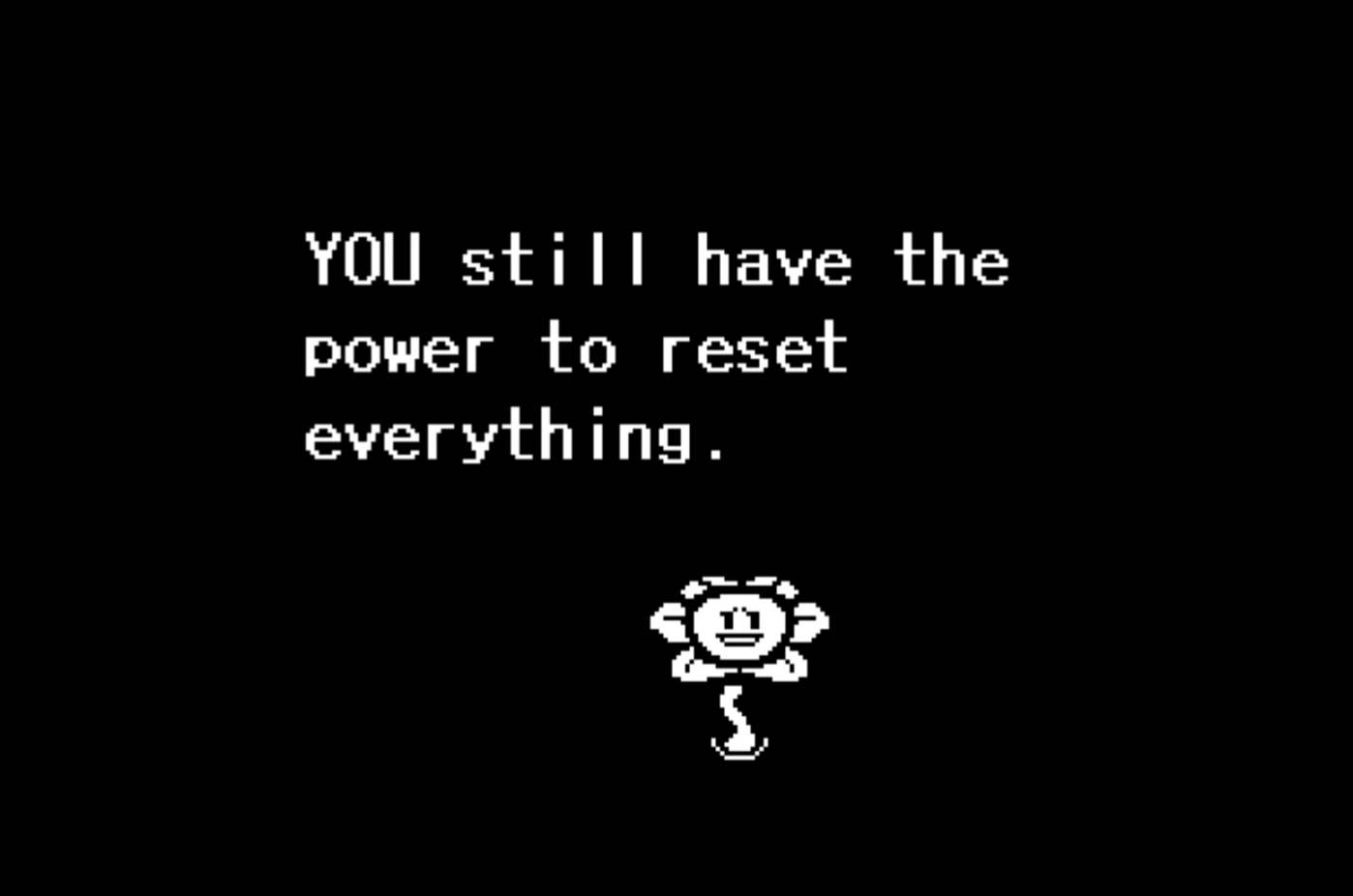

Perhaps most poignantly, we have the unique power to reset the game. Textually, playing it all over again would undo the kindness of a happy ending; the choice not to play becomes a very powerful one, knowing that the characters may be better off if you exit the game after reaching its best possible outcome. It’s not just a matter of player choice and response — it becomes a larger question of what this world will look like when we’re gone, shaping not only events in the present during our playthrough, but also the lasting legacy of our influence.

While the game is widely celebrated for its emphasis on player choice (and interrogating those choices), it also contends with choices we didn’t make — there are many aspects of Undertale that exist extant to the core gameplay itself in a liminal, out-of-bounds space that is simultaneously within and beyond the game’s basic structure.

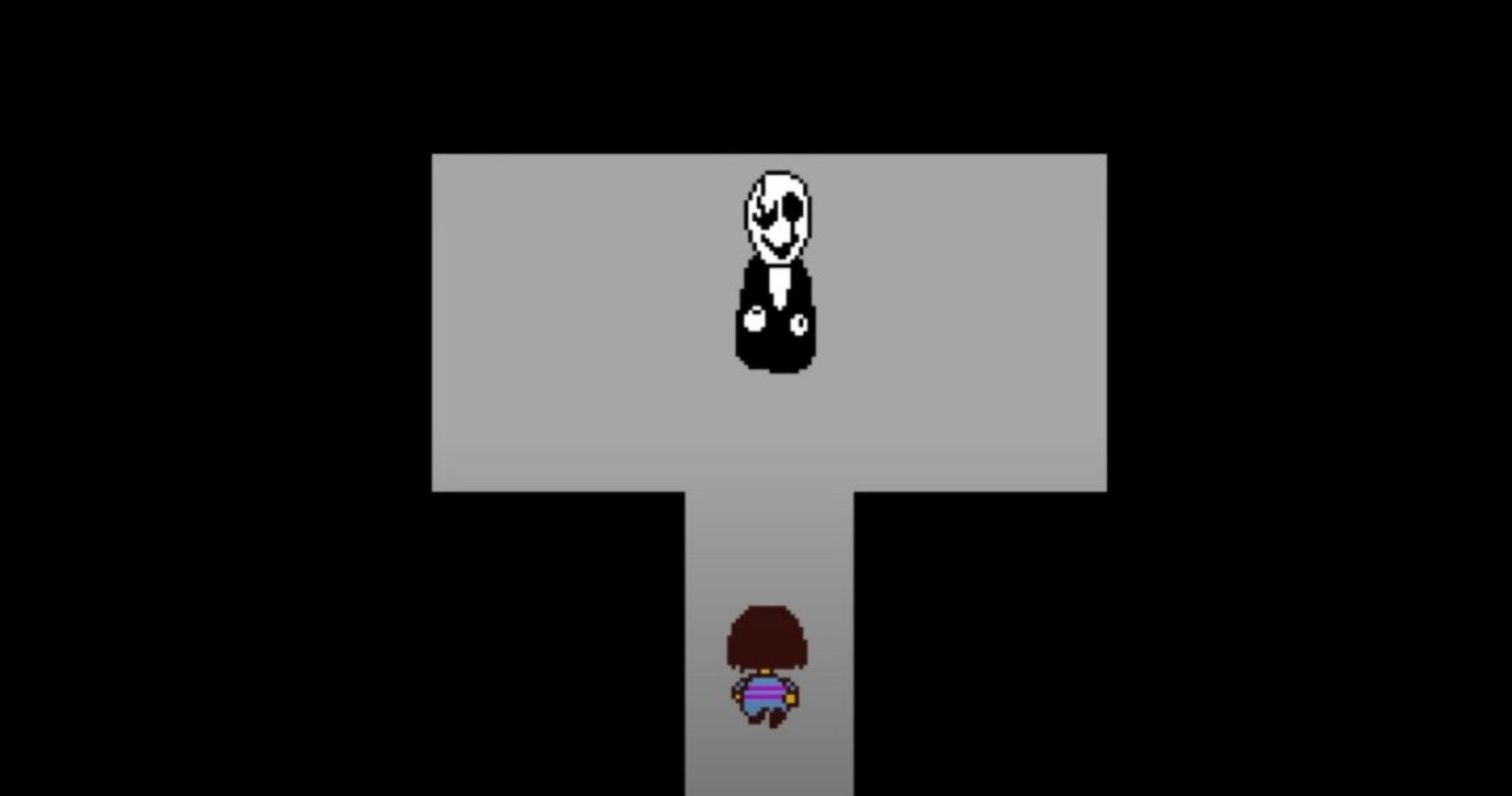

The quest to find Dr. W.D. Gaster takes place almost entirely “outside” of Undertale. Players were encouraged to datamine the game and its website in search of hidden messages about this mysterious man, tucked between lines of code. Alongside these messages, players succeeded in locating extra rooms in the game’s files that can’t be accessed through normal gameplay. To enter these spaces, we must tamper with the game’s reality as a god, rather than a player.

Unlike most aspects of Undertale, Gaster is the one figure that our choices can’t touch. Whether we want to save or destroy what little remains of him, we cannot. Regardless of our attempts to reset the game, our most powerful capability as players, he remains inaccessible. None of the game’s characters seem to remember him (aside from seldom-seen NPCs), or even recognize that he once existed. He exists in our harddrives even when we aren’t playing Undertale, because he cannot participate in its events. Instead he waits for us to uncover the truth, confined to an unknown void space.

Giving Undertale a truly happy ending means leaving it behind — An Outcry, a recently-released RPG Maker horror game, offers a similar choice-based resolution to its story.

An Outcry calls into question the choice to ignore the fires burning at our doorstep. It reminds us to never become complacent or take our relative comfort for granted during the insidious rise of global fascism. As players, we have the choice to either embrace this warning or look away — the protagonist is imprisoned by our whims, and will do as they are told. If we allow the protagonist to overlook the signs of a bloody coup, our worst fears are made manifest: a flight of shrikes with flames in their eyes descends upon Vienna, Austria, and swiftly forces humanity to surrender (in a manner that deliberately evokes Austria’s own surrender to Nazi Germany during World War II). These shrikes feed the ire of crooked politicians and convenience-store extremists, stoking the sparks of their hatred in order to take control of mankind. And in our ignorance or refusal to fight back, we hand the fascists the keys.

After making a series of poor choices leading to this outcome, An Outcry offers players one mercy: there is a way for the surviving characters to simply exit the world of the game. During this route, the protagonist is represented at times by a puppet; our influence lies in pulling their strings, and in so doing, perhaps posits that the protagonist (and by extension, the game’s self-contained universe) would be better off without us.

Our choice to leave is represented through the lens of a theater, a recurring motif in the story: we exit stage left and descend a small staircase toward a closed door. The protagonist steps through it, followed by their best friend, Anne. The two of them glance back at the player before stepping outside; we are left behind, forfeiting our role as the puppetmaster. In so doing, we give these characters a chance to have better lives beyond the bounds of the game itself. They are free to exist in a world without our influence when the curtain falls.

In a way, it is a peaceful parting — when letting the main character go, we offer them a chance at redemption, and ourselves a chance to reflect on the game’s events. What could we have done better? How could we have helped the game’s residents, rather than hinder them?

A beloved cult classic, Moon: Remix RPG Adventure both answers and refutes this question of player harm. In Moon, a character known as the Hero represents the typical player of an RPG — they kill monsters along their epic quest to slay a dragon living on the moon, which will supposedly usher in an era of peace for the kingdom. As such, half of our identity as the player is telegraphed onto the Hero: a violent, malicious figure who plays the game as any other classic RPG protagonist would.

The other half of the player’s role is to thwart the actions of their own shadow. We see beyond the “Fake Moon” presented in the game’s intro, instead living in the “Real Moon”. Existing in this alternate reality means that we see the world’s residents as more than blobby caricatures and mindless beasts — they’re creatures who have committed no crimes, simply living out their endearing, cartoonish absurdity. Notably, they are referred to as “animals” instead of “monsters”; instead of fighting, we are tasked with reviving them after they’ve been slain by the Hero. By solving abstract, lateral-thinking environmental puzzles, we can restore the animals’ souls to their bodies, and perhaps stop the Hero from killing the dragon who lives on the moon.

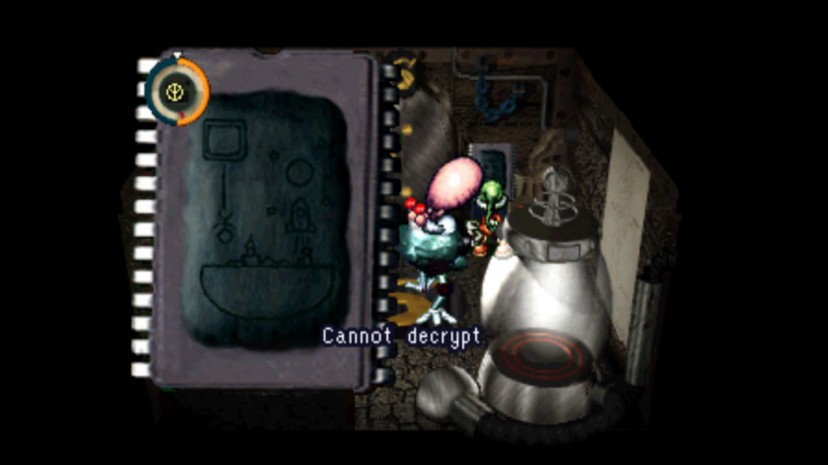

More important than the dragon up there, however, is the conspicuous pile of memory chips. These chips, called Rumroms, contain the data for every character’s actions in the game — they are meant to represent read-only memory chips that would have existed in older consoles, like the Nintendo 64. Every loaf of bread the Baker makes, every bone your beloved dog Tao eats, every night that a drunken man tells you he’s divorced at the local bar, all of the minutiae of Moon can be attributed to these scraps of metal and plastic lying in a crater in space. And so long as these chips lay there, the world will continue to exist. The residents of Moon will live their simple lives on schedule, blissfully unaware of their starbound code.

And yet, they will not be truly free this way; even if they exist without player input, they are trapped in the Hero’s cycle of wanton slaughter. The characters beg the player to “open the door” — a mysterious door that sits atop the pile of Rumroms. We don’t know how to do this until the game offers us one final choice: to open our own doors and step outside, or to continue playing.

“Going outside” in Moon isn’t a message that games are poisonous or a waste of time — it is the opposite: a celebration of what games mean to us, and the many lives they take on beyond their original functions. The residents of Moon also live with us, in our own world: seeing the characters projected into live action photographs during the end credits reminds us that the game will continue to inspire others if we take it with us. Moon lives in our imagination, and can do and be anything that we envision. Whatever we write, draw, or daydream about its characters can be part of their newly unscheduled, unpredictable lives.

A game is bound to its code only within itself — it is a space of infinite potential energy that fuels our interpretations and creativity. What a game gives to us, we give to the game in absentia: leaving it on a high note, sharing it with friends, stepping back as an act of mercy, writing sequels in our dreams, even making two characters smooch on paper, all of these stories exist among the innumerable lifetimes of a game’s legacy.

The world of a game, even one that doesn’t function without a player, will always exist apart from its code, so long as we remember it fondly.