How Moon Defines the ‘Anti-RPG’

Moon is eager to defamiliarize itself. Upon boot-up, after being presented with company logos for ASCII Software (Moon’s publisher) and Love-de-Lic (Moon’s developer), players are taken to the game’s title screen, featuring only a crayon-like drawing of a television set, and overlaid with ominous, green-black static snow. Above it is Moon’s logo, and below it is a gently flashing “PUSH START” prompt. A discordant electronic tone thrums in the background.

We push start. The static fades, and a young boy–rendered in a similarly scribbly style–enters the frame and sits down in front of the TV. Suddenly, the TV is the frame – the borders of the screen become the borders of a CRT display. On this screen-within-a-screen, we are again presented with company logos for ASCII Software and Love-de-Lic. Several walls of expository text cycle past far too quickly for us to read them. A new title screen appears. Moon, it reads, in a decidedly harsher font.

We push start.

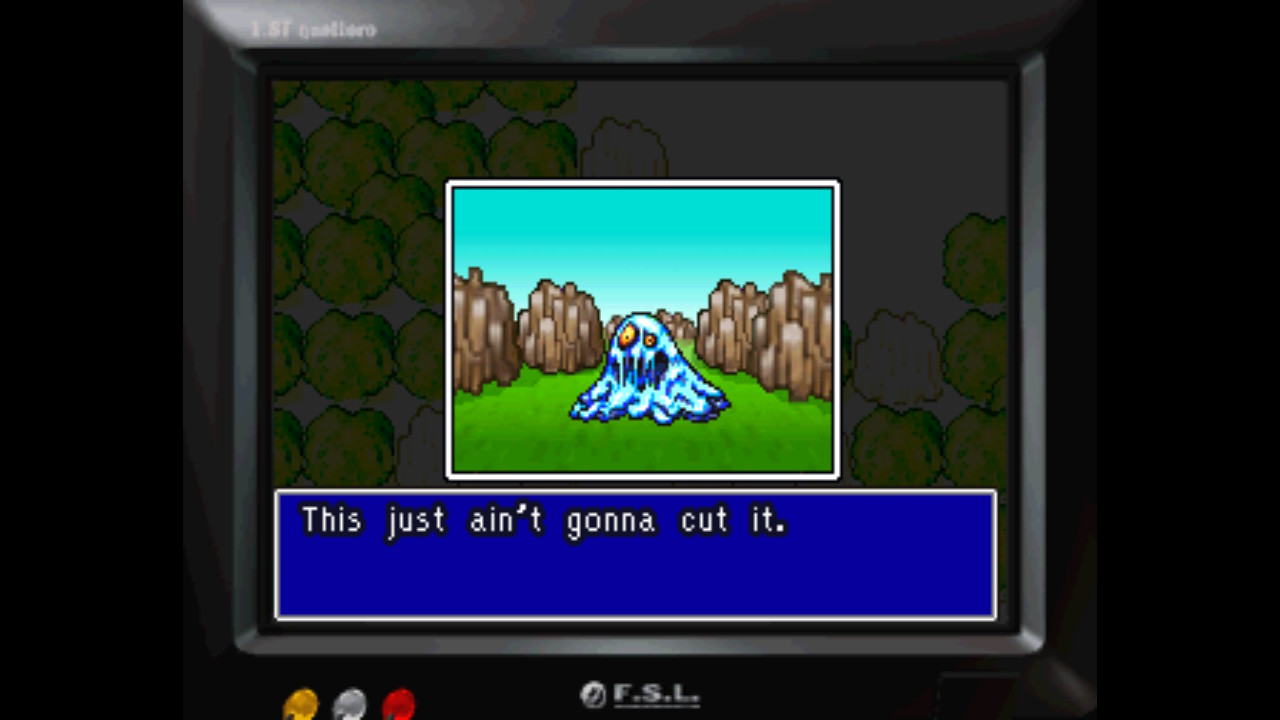

What follows are the opening minutes of an RPG, instantly recognizable to anyone even passively familiar with the genre. Players take control of a hulking, sword-wielding knight dubbed “The Hero,” tasked by “The King” with “slaying the dragon.” “Before reaching thy next level of experience,” the King tells us, “thou must gain 300 points.” We venture into town, and are lauded for our bravery by an assortment of NPCs – one shopkeep is even generous enough to let us poke around in her dresser for “Legendary Armor.” Soon after, the Hero encounters a Slime, with whom he trades multiple light blows before getting impatient and casting lightning magic (“THUNDREXECUTE”). 5 experience points are awarded. Only 295 to go.

This game sucks. It’s repetitive, for one, and slow–every obstacle, enemies included, acts as a half-baked contrivance meant only to stymie player progress. There’s no engagement, no breathing room. Just kill, watch numbers go up, and move on to the next objective. Most of the adventure is elided–the boy, our player surrogate, loads multiple save files, each separated by several hours of playtime–but nothing seems to fundamentally change between that first Slime fight and the eventual final showdown with the dragon, save for how much damage is being dealt (9999, up from 1). After the dragon is hit with a barrage of attacks, the game abruptly ends.

It would be reductive to assume that the Love-de-Lic team viewed all RPGs as monolithically dull. The majority of the small studio’s members were former Squaresoft employees who cut their teeth on Chrono Trigger, Super Mario RPG, and Live A Live, among others–all fantastic games that reflected a keen understanding of the genre’s mechanical, narrative, and visual capabilities. This opening is less a scathing critique than an affectionate (and very funny) joke at the expense of broadly flavorless role-playing conventions, not any one game or series in particular.

Of course, the real game hasn’t started yet. Moon’s parodic first segment also serves as a condensed template for what follows: when the boy is inexplicably warped through his television and into the game’s universe, the proverbial curtain is pulled back. The “real” Moon, as seen through the eyes of an inhabitant rather than a protagonist, is a texturally rich work of cross-genre metafiction that pointedly unspools everything we thought we knew about its world and characters across twenty-odd hours.

As praiseworthy as Moon is as a standalone, singular work of art–and it is a work of art, triumphant in scope and execution–the myth of the analytical vacuum is just that, especially when a game invites comparisons to its forebears so openly: Moon’s description on its official store page labels it an “anti-RPG,” and the original box art bore the subtitle “Remix RPG Adventure.” Discussing it in relation to the games it’s upending is necessary and, I’d argue, only deepens appreciation further. Far from being a simple narrative subversion, Moon mechanically interrogates the tenets central to traditional RPG design, ultimately recognizing and implicating even its own position in the genre’s ever-evolving landscape. More than two decades on, its experiments in form are no less resonant.

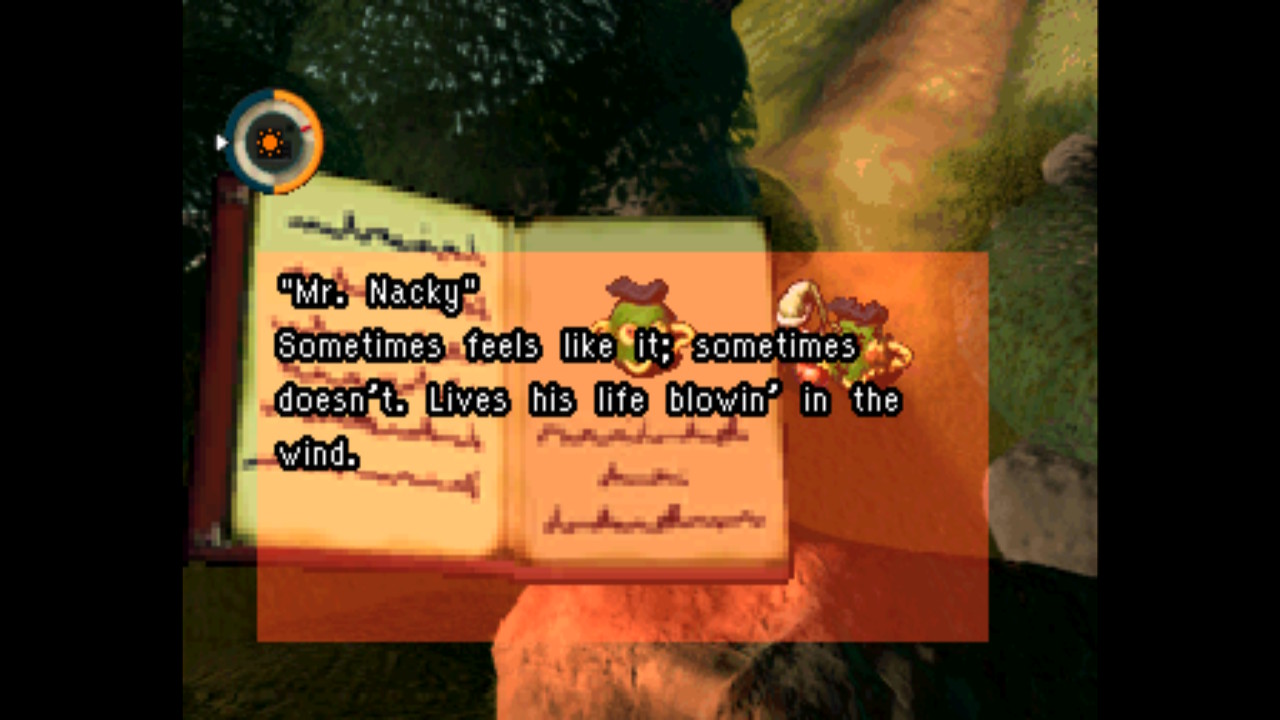

The boy (you get to name him), rendered invisible by his trip between worlds, is asked by a higher power to track down the carcasses of any monsters (or rather, “animals,” as the game goes out of its way to call them) slain by the Hero and “catch” their souls to resuscitate them. This is generally accomplished by reading an encyclopedia entry on the animal in question and solving a corresponding riddle. For example, one animal’s description notes that only those who are “pure of body” can touch it; if you walk into a nearby bathroom, wash your hands, and come back, the soul will be retrievable. There are over fifty such encounters in the game, each rewarding the player “Love” upon completion.

Though these challenges really only comprise a sliver of what makes Moon so fascinating, they provide us with our first and most obvious glimpse at how the designers define the “anti” in “anti-RPG.” Love, in the internal logic of Moon, is the opposite of “experience,” reaped from saving, not killing, animals. Experience, and the strength it begets, can therefore be likened to something approximating “hate,” or at least cold indifference. Moon is distrustful of math; it posits that reducing characters to mere numbers and statistics distances us from their humanity. Saving the animals requires cooperating with them, in a process largely devoid of quantification.

While playing Moon, I thought often of Paolo Perdicini’s “Video Games and the Spirit of Capitalism,” an extensive lecture in which Perdicini draws upon sociologist Max Weber’s theory of rationalization to describe how video games so frequently embody the capitalist drive for efficiency in their design. Violence, relationships, community – all, he says, are flattened into numerals and binaries (visible or otherwise), and presented with little room for alternative modes of play:

“When we produce artful depictions of our world using computers, we inevitably carry over a cybernetic bias that could reinforce certain assumptions and mindsets. From the eyes of a computing machine, everything is mathematically defined and susceptible to rational calculation. Since games are typically goal-oriented, all the elements and relationships within them tend to be reduced to means and ends.”

Perdicini goes on to name several examples by genre, focusing especially on social games like Farmville, and though his points are salient, I’m surprised that RPGs aren’t discussed further. This is a genre brazenly about numbers. Enemies are numbers, resources are numbers. “Optimal” party formations are more likely to be based on how various stats, strengths, and weaknesses interact than any given player’s personal preferences. It’s sometimes easier to think of characters as pieces on a board, as “units,” than as people.

I adore RPGs, I should clarify. Xenoblade Chronicles is far and away my favorite game, and that’s about as RPG as it gets. My goal here is not to pass judgement on the genre writ large, but rather to illuminate how Moon’s deliberate changes in design ethos bring these innate tensions into sharp relief. Granted, Moon by no means eschews gamification, but it is acutely aware of how gamification in RPGs may be construed as pernicious. It sets out not to become formless, but to take on a radically oppositional form.

This philosophy crystallizes moreso in the game’s overall structure than in its individual puzzles. In reality, animal-saving is not the central conceit – passage of time is. More specifically, Moon is about living in a world that exists on its own terms, growing and changing around you without asking your permission. The game runs on a weekly cycle of seven different in-game days, each with day and night phases. This is where Love comes in: the more Love you collect, the longer you’re able to stay awake before collapsing. “Levelling up” in Moon affects not your strength, but your ability to exist, to inhabit.

Its map is designed to accommodate this. The “fake,” RPG-ified Moon seen at the outset suggests linear environmental progression, with the Hero moving from one area to the next in a relatively straight line, the world laid out at his feet. But Moon’s true map, the one you’ll spend most of your time in, is radial and open. Players have the tools they need to access it in (almost) its entirety from the beginning, with the only real obstacle (and it’s alleviated fairly quickly) being a shortage of Love. Beyond that, one need only explore and experiment. Traditional progression is quickly discarded in favor of organic discovery.

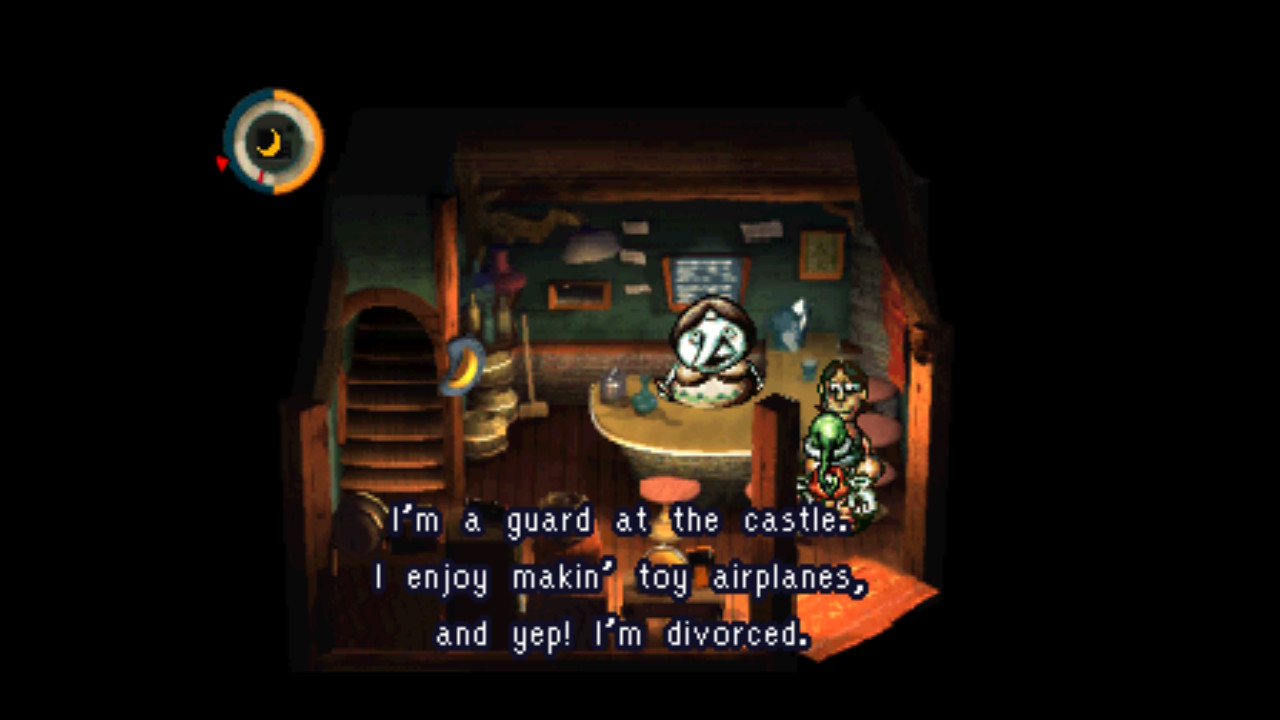

Perhaps most crucially, Moon is lived in. The game is populated by a wide assortment of distinct, eccentric NPCs, all of whom operate on their own schedules and most of whom have individualized quests that, if completed successfully, reward Love. Unlike with the animals, though, hints are scant, and making headway on a quest usually involves a great deal of patience. Talk to the character on different days, see what their routines are, present them with items you think may interest them. Many NPCs have some degree of familiarity with each other, as well, meaning interpersonal relationships are often investigated in much the same way. There are murmurs, for example, about a failed romance between the local bartender and a mushroom-eating, forest-dwelling hippie. And isn’t it strange that the baker never seems to leave his shop, even at night?

Here is where the game shines brightest. Moon’s lattice of character work is staggeringly dense (I’m far from uncovering all its secrets – halfway through writing this piece, I inadvertently discovered a side story about attending night school with a talking bird), stuffed so chock-full of easily-missable dialogue and hyperspecific conditional events that I spent my first few hours overwhelmed at the possibilities, fretting about how to allocate my time. Soon, though, my pace was eased with the knowledge that time limits were, on a macro level, nonexistent. The clock ticks, but nobody is going anywhere. Eventually, I stopped worrying about rigid goals altogether and let myself sink comfortably into the game’s lax design. I became aware of an entire community bustling just outside my door, one which I could affect but not control. I was, in a word, living.

And why shouldn’t an anti-RPG take this shape – that of a game with an immersive, persistent world, fueled chiefly by character interaction and freedom of exploration? Moon theorizes that the mechanical, if not necessarily narrative, viewpoint that RPGs necessitate is limited at best and violently solipsistic at worst. The Hero is unable to engage with anything outside himself: he robs people, kills animals, presumes the adoration of those around him while doing little to earn it. He is not knowingly evil so much as he is a video game character, stripped of all nuance, concerned only with watching numbers inflate. You, on the other hand, are not a video game character, not in the same sense. You’re you. Quite literally invisible, faceless, without prescribed identity, stranded alone in an unfamiliar world. This is not your game. With enough effort, though, it could be your home.

And yet Moon is, inescapably, itself a game. It knows this, and indicates as much in ways both subtle (several in-game “prophecies” are inscribed on ancient slabs eerily resembling computer chips) and obvious (the denouement, which I dare not spoil). It recognizes that it’s not equipped to be the solution to its own problem. Love, ultimately, is just another type of experience point, another game mechanic. The relationships forged in Moon are not real. They are still transactional, a means to an end, and that end can’t, by design, be a simple happily ever after. What good is a happy ending in a world of ones and zeroes?

Moon’s brilliance and effectiveness is attributable in no small part to its air of artistic spontaneity. This was a project that sprang more or less out of extended “jam sessions” between its developers, whose “create now, balance later” approach led directly to Moon’s lush, at times confounding eclecticism. The visuals, for example, are an offbeat mishmash of disparate styles: prerendered backgrounds à la Final Fantasy VII, 2D character sprites à la Suikoden, and, in an inspired flourish, claymation sprites for the animals, created by animating and digitizing actual clay models that team members crafted themselves. As a result, the animals embody a uniquely rough-hewn, realistic physicality, a radical departure from the pixel-art portraits in the opening segment. It’s like nothing else I’ve ever seen, and if this Famitsu interview is anything to go by, it was totally off-the-cuff:

Kazuyuki Kurashima: Come to think of it, all the animals were made of clay, and if people wanted to, they were free to make new animals to put in their own maps.

Yoshiro Kimura: Unthinkable now, right? (laughs) The animal “Tommy” was a doll I made. At first, I tested with Tommy, experimenting with a “Soul Catch” game where you caught the soul of an animal to rescue it, and I remember it being pretty important. (laughs)

Kurashima: Right, Tommy might have a lot of memories associated with him. The animals were also named by the people who made them. With Tommy for example, I saw Yoshi-chan making him from clay and asked “What’s it named?”

Kimura: Since he asked, I thought about it on the spot and replied “Tommy.” (laughs)

Kurashima: And as for the animals appearing on each map… We’d line up all the dolls everyone made, and everyone could take whichever they liked to use as they wished.

The entire interview is filled with similar anecdotes, if you’re inclined to read it. Stories of developers using empty fruit boxes as desks, of ad-libbing ideas and assigning themselves roles, of sitting down and just creating.

Moon is, miraculously, unpretentious. It is a game born not from ill-conceived notions of intellectual superiority or moral didacticism, but from a group of artists who loved thinking about video games, who wanted us to love thinking about video games. Their abiding passion for the medium echoes not only in the big emotional beats and metatextual queries, but in the quiet, ephemeral touches, like the PS1-compressed snippet of “Clair de Lune” crackling softly on your grandmother’s radio.

“That is love, this is love.”

1 thought on “How Moon Defines the ‘Anti-RPG’”