Provided by Raw Fury

On Bad Endings: Resistance and Meaning-Making in the Apocalypse

In the first act of NORCO, you stumble across a surreal shadow puppet play under a highway overpass in New Orleans. In the play, an alligator tells her life story: Once captured by a local fisher who kept her as a pet, she escaped during a catastrophic flood and now finds herself hunted by the local shrimpers. “They hang hooks from the trees with chicken thighs. They shoot bullets in our heads behind our eyes. It is a curse that I am the last to survive,” the alligator laments.

A metanarrative minigame follows in which the alligator asks you to take revenge by killing the shrimper who killed her last child. You can choose to resolve the alligator’s plight in different ways, but, if your role-playing instinct takes over and you savescum to try out the different options, you’ll notice that none of them result in a neat resolution. Whatever you choose, the alligator’s curse lingers; the bayous remain haunted by vengeful spirits. What will you do when you realize that there’s not going to be a happy ending?

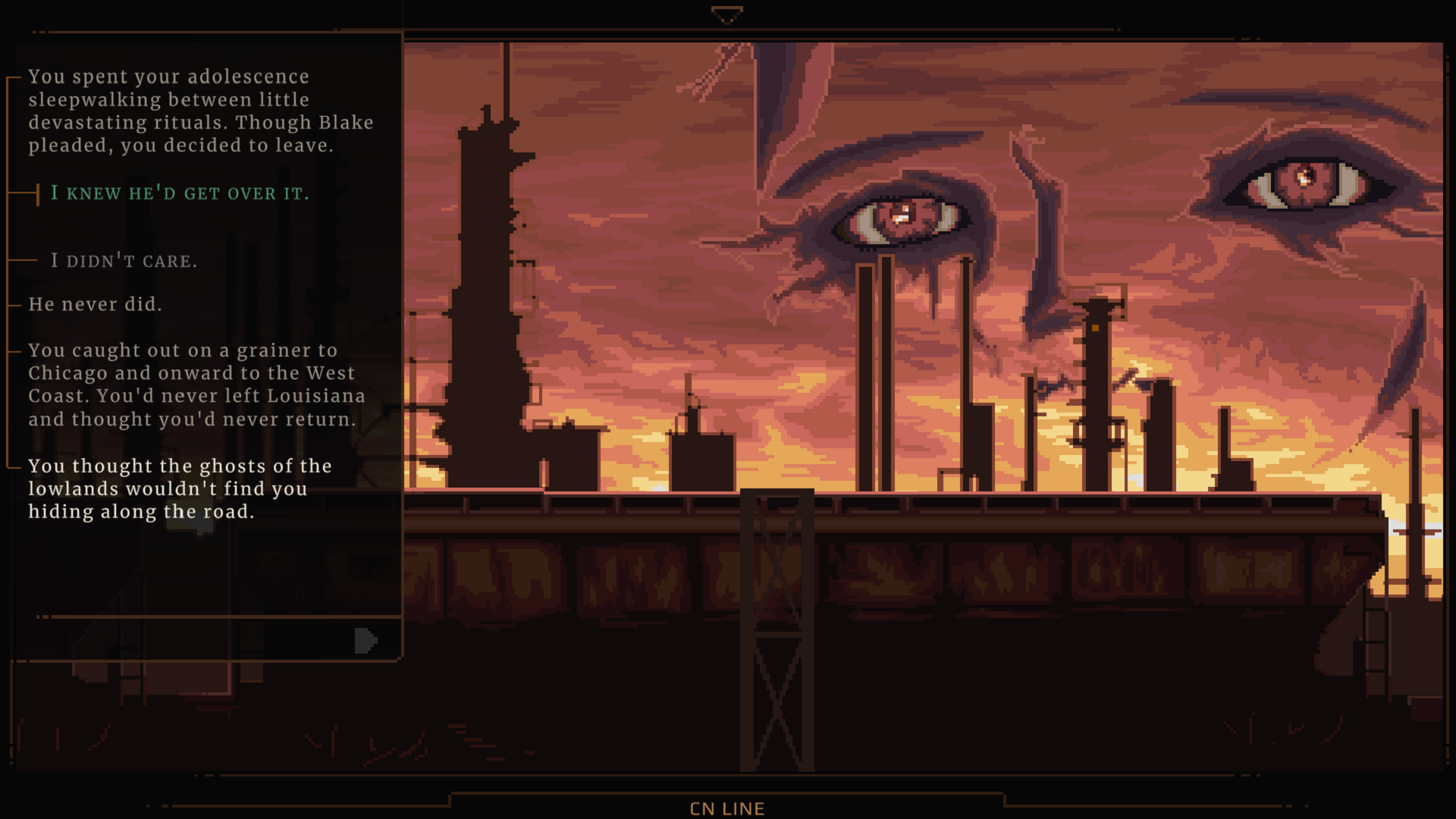

NORCO, the new point-and-click adventure game from Geography of Robots, is perfectly comfortable leaving the player unsettled. Set in a gloomy landscape of oil refineries and swamps outside of New Orleans, the game explores the violent impacts of capitalism and the fossil fuel industry through the story of Kay, a 20-something former resident who has returned to Norco after her mother’s death from cancer and her brother’s sudden disappearance. It’s a testament to the quality of the game’s writing that it tells a story in this setting without being didactic; the bleakness of the surroundings are balanced by the beauty in the pixel art, the game’s sense of humor and a wide cast of characters who feel real. These characters all find different ways to escape their reality through drugs, video games, or the idea of off-world colonization. But you, the player, are subtly confronted with the futility of it all—no one has a solution to the fundamental problems in this world; no one offers a path to overthrowing capitalism or repairing the harm caused by Shield Oil (the real town of Norco, LA, is the site of a Shell refinery). Some reviewers have found hope for a better world in this game, but I read it differently: I think it is a story about making meaning in our own hopeless world.

You could imagine a different take on this story, one that plays into a common video game-y impulse toward power fantasies and happy endings. You could make a NORCO where you can spray away all of the smoke discoloring the horizon or wash the toxic waste from the waterways, Super Mario Sunshine-style; you could make a NORCO where you team up with the other locals to kick AI ass and take over oil refineries, Tonight We Riot-style. (You could argue that we got this game already in the beginning of Final Fantasy VII.) The NORCO we get, however, eschews such hopefulness, presenting simply the dire reality confronting individuals in ongoing ecological catastrophe.

While NORCO has been variously described as sci-fi, magical realism, and dystopian fiction, the hopeless reality it presents doesn’t feel so far-fetched; we’re not exactly faring great in the real world right now, either. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released another report on April 4 echoing what has been common knowledge for decades: drastic action is needed to mitigate escalating climate catastrophe. As Andreas Malm points out in How to Blow Up a Pipeline, despite years and years of similar reports, the fossil fuel industry continues to build pipelines and power plants; this suggests that they expect minimal resistance to decades of returns on their investments. They know that capitalism has consistently proven itself to be more resilient than predicted, surviving and thriving through its contradictions, even while these contradictions become more and more transparent.

You may think that such pessimism is counterproductive or unimaginative, or you may even think that this line of thinking is dangerous and anti-revolutionary. Often mainstream socialism insists on optimism as a precondition for revolutionary action; no one would want to fight if they didn’t think they could win. This logic dates all the way back to Marx’s own dialectical materialist view of history, which carried the base assumption that we would pass through capitalism, into socialism, and finally beyond, into communism. The result is that mainstream socialist ideas are rooted in a progressive understanding of history, in which things must get better over time. The collapse of capitalism and the rise of proletarian revolution, if not inevitable, is at least something we are expected to believe in with near-religious faith.

As a result, anti-capitalist video games enter into a doubly optimistic space: video games, which traditionally are designed to make victory attainable to the player, and the Left, which traditionally anticipates the victory of communism. In both cases you’re liable to find the same rhetorical question: if you don’t think you can win, then what’s the point? This can certainly lead to feel-good stories about the triumph of the proletariat, but it can also be a prime vantage point for examining the limits of optimism itself.

Take 2019’s Disco Elysium, for example. It’s been a point of comparison for NORCO, as another point-and-click adventure game driven by ambitious writing. In addition to its quality narrative and world-building, Disco is noted for its communist overtones; the developers from ZA/UM famously thanked Marx and Engels in their Game Awards victory speech. Disco doesn’t have a particularly optimistic outlook for communist revolution, however. The game is set in a fictional world where the communists have already won and already lost—forty years later, you’re a drunk and amnesiac cop cleaning up a murder in the ever-lingering aftermath. While the game is not shy about poking fun at fascists and neoliberals, role-playing as a communist doesn’t net you much in the game, either. Pursuing the “Mazovian Socio-Economics” thought decreases your character’s Authority and Visual Calculus stats, highlighting the way that embracing a materialist critique can sometimes just make it harder to exist in the world. This didn’t resonate with all of the game’s players on the Left. Writing for Vice, Colin Spacetwinks wrote that: “For even the most materialist of materialists within socialist and communist thinking, this is still an ideology, a philosophy, tied up in hope. It requires a belief that a better world is possible, that we can, should, and will do more for each other.”

But is that belief always good? In their 2011 book Cruel Optimism, Lauren Berlant describes scenarios in which hope and desire actually make things worse: “[a] relation of cruel optimism exists when something you desire is actually an obstacle to your flourishing.” Discarding cruel optimisms, while often nearly impossible, opens up new possibilities for action and meaning-making. Disco excels at highlighting the cruel optimisms at play in its world—the moralists’ neoliberal concern with market stability lead them to contradict their own stated ethical commitments, the cryptozoologists’ obsession with discovering a rare insect lead to the deterioration of their health and relationships. The game’s communists are not exempt—those that remain are haunted by a foreclosed communist future, doomed to live sad and bitter lives at the edges of society. Ideological optimism in Disco Elysium, rather than serving as a prerequisite to action, generally stifles it.

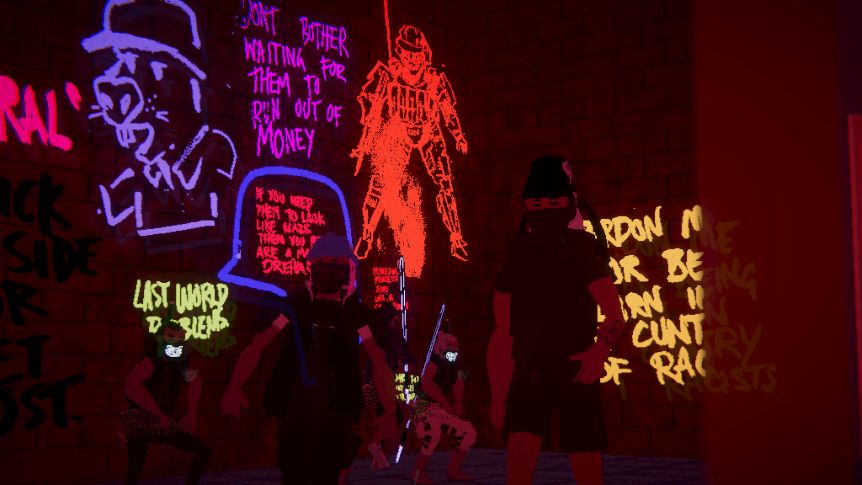

In the end, however, Disco Elysium can’t avoid its own cruel optimism. While the game offers rich critical possibilities for players who choose to play Harry as a fascist, I’ve never been able to stomach those dialogue options—I’ve generally stuck to playing Harry the friendly communist cop. Stick to playing this way, and the game gives you a shot at a happy ending, in which you solve the murder and the zoological mystery, reconcile with your precinct, and even have a transcendental experience in which an otherworldly being tells Harry that he is the embodiment of hope for humanity. It’s an uplifting ending that ties up all the loose ends, but in so doing it reveals a limited imagination for change. The game offers glimpses of radical acts, like in the street art of Cindy the SKULL or ravers converting an abandoned church into a nightclub, but in the end, all of these acts are contingent on the participation of a benevolent police officer. Instead of exploring new possibilities of resistance in the face of a failed revolution, Disco Elysium presents the contradictory idea of a good cop who likes to talk to people.

A game that avoids such narrative trappings is 2020’s Umurangi Generation, a photography game set in an apocalyptic Aotearoa. You navigate the game with a camera, documenting specific images you’ve been commissioned to photograph for a newspaper, while also capturing the world and its inhabitants to your own liking. The game is influenced by indigenous philosophies of Respectful Design, in which agency is given to the community; while there are main characters, major events, and lore, the player makes meaning of all of these elements on their own by navigating the environments and selecting what to photograph. That isn’t to say that the game doesn’t have explicit messages. Naphtali Faulkner, the game’s solo Maōri developer, is explicit that the game is a critique of neoliberalism and its failure to respond to climate change. This critique is often communicated by object positioning and scale in the game, most notably the size of the unprecedented ecological apocalypse and the size of the global fascist response to it. It’s inarguably apocalyptic.

Despite this, Umurangi Generation and its prequel DLC, Macro, capture numerous examples of collective resistance and struggle—even as the city is on police lockdown, even as the world is ending, you witness queer and indigenous folks partying in the streets, making defiant artwork, and, above all, caring for one another. It resembles what the anarcho-nihilist author Serafinski describes as ecstatic joy or jouissance: “that which animates resistance for its own sake so that even if we have no future, we can still find life today.” The people of Umurangi resist and rejoice in spite of the impending doom visible on the horizon—they have no reason to believe that their collective struggle could match the scale of the catastrophe, yet they rebel.

I don’t mean to argue that Umurangi Generation is an anarcho-nihilist game. While the game’s approach to design makes that interpretation possible, Faulkner has talked about various optimistic interpretations of the ending of the game and the Macro DLC. I should also be clear that I don’t mean to shame anyone who believes that capitalism can be dethroned. But we ought to consider what our resistance should look like if it turns out that we can’t overthrow capitalism. What possibilities for meaning-making and action open up to us beyond trying to min-max the revolution?

In a batture behind an automated convenience store in NORCO, you run into someone named Lucky, renowned for having blown up an oil pipeline. If you ask him about his ecoterrorism, however, you’ll find out that he’s not in it for ideological reasons at all. “Lucky done blown up all kinds of shit. […] He just like causing trouble,” he explains. For him, there was no consideration of the odds of success, no calculation about the possible impact of the pipeline explosion on the fossil fuel industry as a whole, no grand plan to save the world. Lucky simply decided to blow up a pipeline. As Serafinski writes, “[t]here are no demands to be made, no utopic visions to be upheld, no political programs to be followed—the path of resistance is one of pure negation.” I can’t agree with Lucky or Serafinski entirely—despite it all, I’m still clinging to visions of a better world—but we could stand to learn from the commitment to resistance for its own sake. For if we only act when we think we can win, we may not act at all.

If you like what we do here at Uppercut, consider supporting us on Patreon. Supporters at the $5+ tiers get access to written content early.

1 thought on “On Bad Endings: Resistance and Meaning-Making in the Apocalypse”