Prison Empire Tycoon as a Case for Prison Abolition

Defunding and abolishing forms of policing and imprisonment is fundamental to creating a safer world for Black people, and the summer of 2020’s rallying for the Black Lives Matter movement has brought that message front and center on a global stage. This aim of removing police and prison power in the U.S and worldwide, is tied to abolitionist activists’ long running attempts to disentangle an entire criminal justice system designed around racial discrimination.

As Angela Davis outlined in 2003’s Are Prisons Obsolete?, modern America’s prison system, as exported globally, was formed in the image of the post-slavery approach to restricting the lives of Black Americans (p.37). The post-abolition institution of state-wide Black Codes by many states targeted free Black individuals as criminals under broad conditions, and punished them with imprisonment and forced, unpaid labour under lease. The morphing and modern replication of these racist approaches to arrest and incarceration post-civil rights has resulted in sixty years of rapid growth of American prison populations, to over 2.3 million people, 40% of whom are Black.

What’s more, the enforcement of prison labour, either underpaid or entirely unpaid, and the exploitation of this by private prisons, has led to an unavoidable, unsettling message echoed by abolitionists: slavery never ended.

Codigames’ free mobile game Prison Empire Tycoon, released on iOS and Android in late April 2020, is perhaps the best recent case in gaming for abolishing this system. Amongst the Madrid studio’s several releases in the idle tycoon genre, Prison Empire is the one that gets closest to the darkest forms of capitalist exploitation, alongside their mid-July release of Idle Police Tycoon. The semi-automated systems of supply/demand, investment and profit in idle tycoon games (management sims’ lite, mobile cousins), lead to addictively rising stakes— with a healthy dose of advertising and microtransactions to encourage faster success and actual investment in their virtual economies.

Prison Empire’s version of this asks you to invest in the privatized prison industry. The game allows you to build prisons perfectly designed for making cash-money off of the backs of a human supply chain. Your aim is to ‘reform’ as many prisoners as you can in order to hit your quotas and make that money. Prisoners are reformed by upgrading prison facilities to liveable standards and dealing with their accumulated needs as represented by satisfaction meters. The lower the meters, the more stressed your prisoners become, and the more likely they are to riot, meaning they’ll be transferred and, unless highly militarized, your guard staff will quit. You don’t want that.

During the period of time where ongoing protests for Black lives occupied media attention, peoples’ hunger to be in control of the reigns of the prison-industrial machine sent downloads on the Google Play store to 5,000,000+ and counting.

While public ownership is the case for the majority of prisons, the game’s picture of corporate expansion is a passionate imagining of how the current growth of private interests in the US system could be furthered, in line with Davis’ assessment of prison having moved consistently away from being a place of reformist penitence to one of forced isolation and labour (p. 57). On starting the game you’re told by your head guard that:

“Prisons are subsidised by the state, so we get government money every hour of the day… The state also pays a set fee for each hour a prisoner remains in the prison. Finally, if they serve their sentence and are reformed, we’ll also get paid when they leave. It’s a perfect business!”

Reading like a capitalist’s dream of the ultimate prison, this form of justice is criminal based fully around the eugenic ideas of the criminal, and human assets, relying on constant supply, which the game provides, and the vision of the incarcerated person as an asset, validating their total dehumanisation. While the rise in prison populations is mainly driven by antagonistic, racist policies over minor infractions, the game’s vision is of the prison as the perfect private profit machine, an idea so inhumane that it would be satirical if the game didn’t fully insist on the reform of its prisoners via commodity without comment. As the head guard makes clear from the get go, these people are ‘scoundrels’, ‘riff-raff’ and ‘misfits… but at least we’ll make good money from them!’

The game coats all of that in the serotonin boost laden UX of idle reward while these criminals sit under your thumb. Reading the FAQs on Codigames’ site unintentionally provides a window into the eugenic mind of this reality.

Away from the game’s capitalist obsession, another idea that dominates cultural perception is that the basic running of a prison, in line with a prisoner’s human rights, will be rehabilitative. This is what runs Prison Empire’s entire reward system model. While it seems like a neutral idea, the game’s beginning makes it clear how a mismanaged prison culturally allows us to see ones that sustain basic living conditions as exceptional by prison standards. You begin housing inmates well before your facility is safe to live in, meaning that the game insists, by its idle system of reform profits, that you can correctly house and rehabilitate inmates in facilities without places to even wash clothes or provide medical treatment. The normalisation of this in Codigames’ design shows that the idea of prison that has permeated culturally is one of the permission to violate the basic human rights of those inside. This isn’t just the developers being humorously clueless, since the idle state they designed came from the shared western perception of prisons. The original prisons you work with in game violate almost all possible codes in the UN’s outlines for treating prisoners.

By 2003, as Davis’ states, this was already normal to us (p.81). Just as we envision all police as corrupt, having our storytellers acknowledge this while maintaining the heroism of the rogue cop, our modern prison narratives ruminate on terrible places, where mostly terrible things happen, but ones we just have to try and improve. This has continued throughout the Covid-19 pandemic. People are dying in detention of a disease without cure, because the prison is not a place for human justice or penance, as they are idealistically imagined by Prison Empire’s reformist ideology. These are places where the conditions don’t matter, not really, because it’s where we allow the police to put people we want to forget, and who those in power not-so-secretly want bad things to happen to, they are places designed and maintained in an inhumane manner in order to allow social torture. This is not a subjective opinion. Look around. And beyond America look to the conditions in Australia for Indigenous people, as reported in Nayuka Gorrie and Witt Church’s call for abolition, protesting the conditions of Indigenous targeted youth imprisonment by the state that was built on colonial prisons.

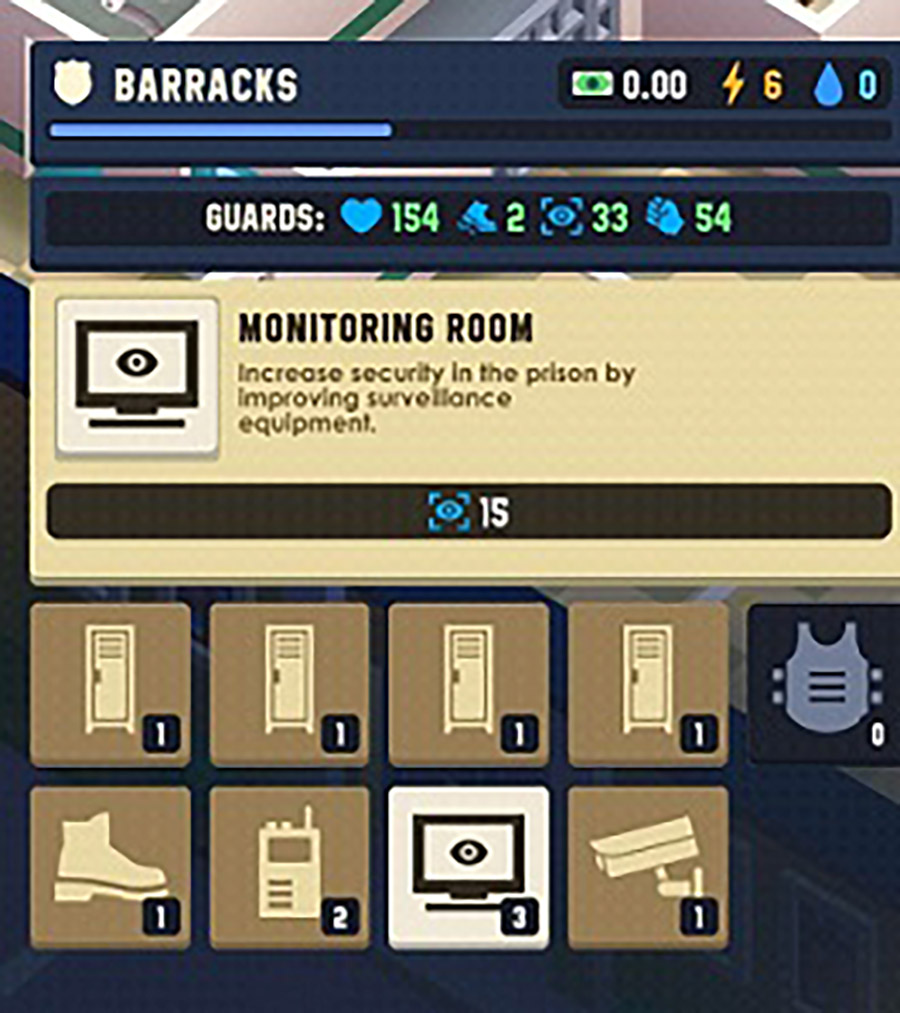

Ultimately, Prison Empire takes its lead from Prison Architect, the successful, BAFTA winning, prison management simulation developed by Introversion. Since that game’s early-access release in 2012, and its subsequent acquisition bypost its new ownership by multi-studio publisher Paradox Interactive in 2019, it has had its own problems with facing the reality of prison. In a statement made on Prison Architect’s dedicated Twitter account on June 10th, 2020, the team announced a delay to upcoming DLC, and clarified that the game’s intentions have always been based in caricature, knowing that they deal with sensitive topics, and holding off on updates ‘to let more important voices be heard.’

The fact that the statement reads more like an apology note shows the team’s knowledge, if not will-to-act, ofon the game’s inherent promotion of a racially intolerant system. This may have something to do with its historic failure to acknowledge racial injustice. A 2015 interview with Introversion’s white, British head developers, Mark Morris and Chris Delay, by Shane Bauer, shows how much care they had for these factors during development. Claiming their objectivity, Morris stated “we are not prison reformists… there is no agenda here”, before responding to a question about the lack of racial structures in the game by admitting that they’d ignored that factor, having not wanted to pay “lip service to the issue.”

Six days after their statement, the Prison Architect team announced their new DLC – Island Bound.

Codigames has made no statement about racial justice, nor any promotion of their game on social media, and Prison Empire, in its earnest presentation of a prison system that ‘works’, feels like it has emerged as the unironic result of Prison Architect’s wilfully ignorant design.

Thinking past these power fantasies and towards abolition, Davis’ points to the historical importance of prison literature reaching the outside in creating awareness, and visions of games and art that embrace prisoner solidarity, rejecting Codigames’ and Prison Architect’s irresponsible visions of prisoners, should be part of an abolitionist future. In 2016 the artists Larry Achiampong and David Blandy worked with prisoners, paperless migrants, and young people to create FF (Finding Fanon) Gaiden, giving them a version of Grand Theft Auto V to create their own machinima, edited videos of gameplay, layered with voice overs of stories they wanted to tell.

The videos are an expansion of the artists’ collaboration considering the thoughts of Frantz Fanon, the radical Black thinker, by tracing personal interactions with race, globalisation, and identity in GTA V’s cold digital satire of America. While the project is small, ending up living in the usually limited sphere of contemporary art, the way Larry and David described smuggling a PS4 into prison as a covert operation at a talk in Edinburgh in January, and the experiences of Larry’s uncle in immigration detention, made it clear that they wanted the voices of the incarcerated and vulnerable amplified by their work. It reinforces to me the essential point that steps towards abolishment are achieved in raising up the voices of the marginalised, all the emotions therein, and not in the white apologetics of certain studio’s responses to Black Lives Matter in 2020.