Provided by Ghost Pattern

Review: Wayward Strand is a New Classic of Video Game Storytelling

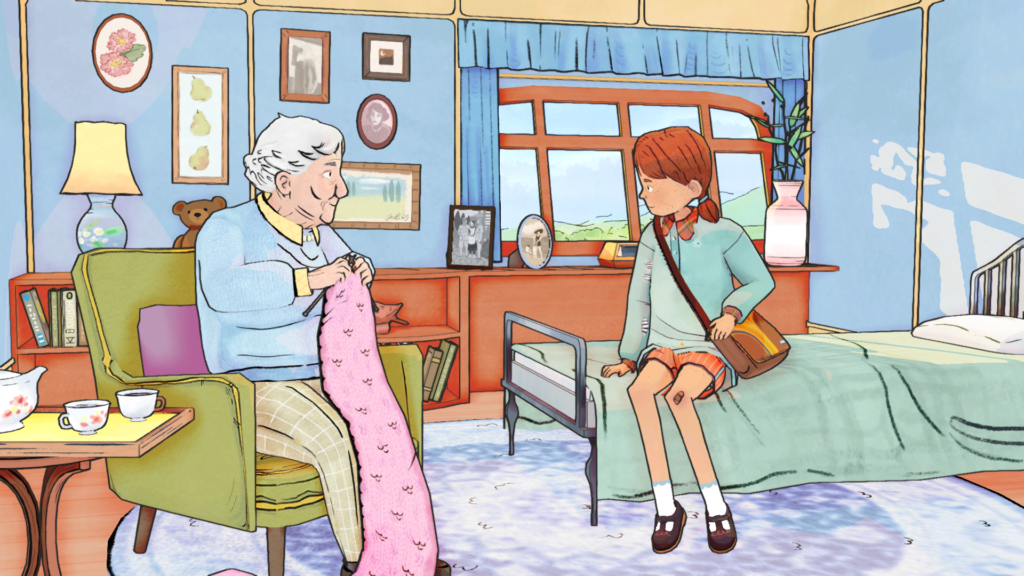

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: Majora’s Mask, but in the geriatric ward of an airship-turned-hospital in 1978 Australia.

Still here? Thought so. Truth be told, I’m being reductive; the elevator pitch leaves out huge differences like no time-rewinding, no dungeoneering, and no combat of any kind. But Wayward Strand does ask you to play out three in-game days in a world where time passes regardless of whether Casey Beaumaris, your fourteen-year-old avatar, is present to witness an event and record it in her notebook. The result is an uncommonly grounded and mature narrative that elevates Wayward Strand to nothing less than an essential text, a must-play for anyone who cares even a little bit about how video games tell stories.

Up in the air

Casey isn’t supposed to have her notebook. Her mother, the harried head nurse of the airship/hospital, scolds her to that effect on the ride over, having brought her along during a school holiday. With only two (formerly three) nurses for six (formerly seven) patients, the ward is spread thin. Casey is there to help out, tending to the patients and keeping them company for some labor of the good old fashioned “unpaid but at parental demand” variety. But Casey is also a very serious journalist for her school paper, and she wants to gather material for a prospective article about the airship.

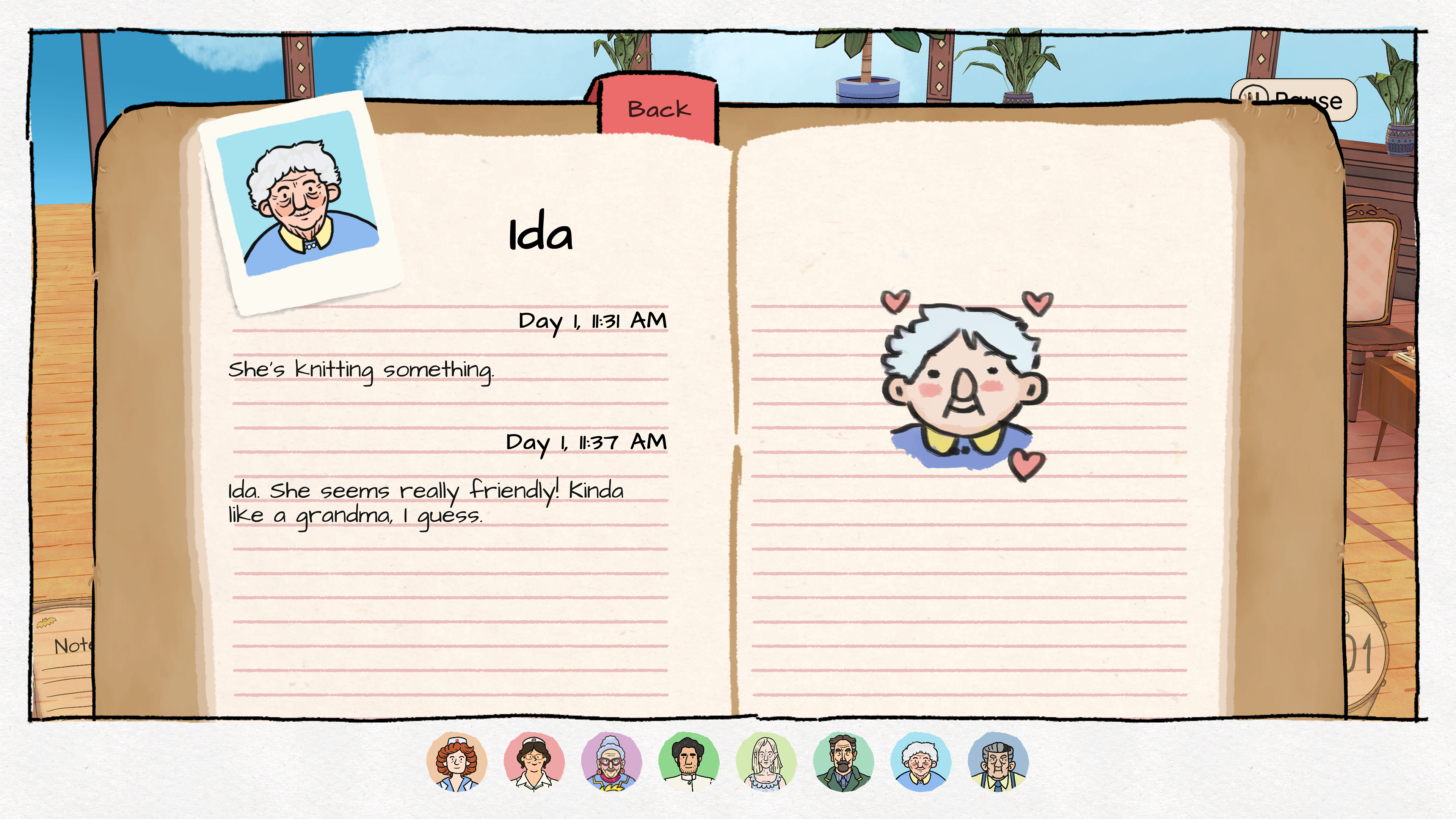

Hence the notebook she’s stowed in her bag. Quite unlike Majora’s Mask, the notebook is not very helpful for navigating the game; save for the lunch hour and one wheelchair-bound patient who keeps a tight schedule, the characters perform different actions each day. Rather than a log of who goes where at what time, Casey fills her pages with observations and doodles, more akin to an actual notebook for her own reference at some point beyond the bounds of the three-day story.

By the end of the game, rather few of Casey’s notes are about the airship. The whole apparatus is a bit of a red herring, providing some initial direction for who to visit, but quickly becoming the least interesting detail about Wayward Strand. What becomes your main concern is altogether less fantastical: the rich lives of the patients and workers in the ward, all of it extensively voice acted and impeccably written.

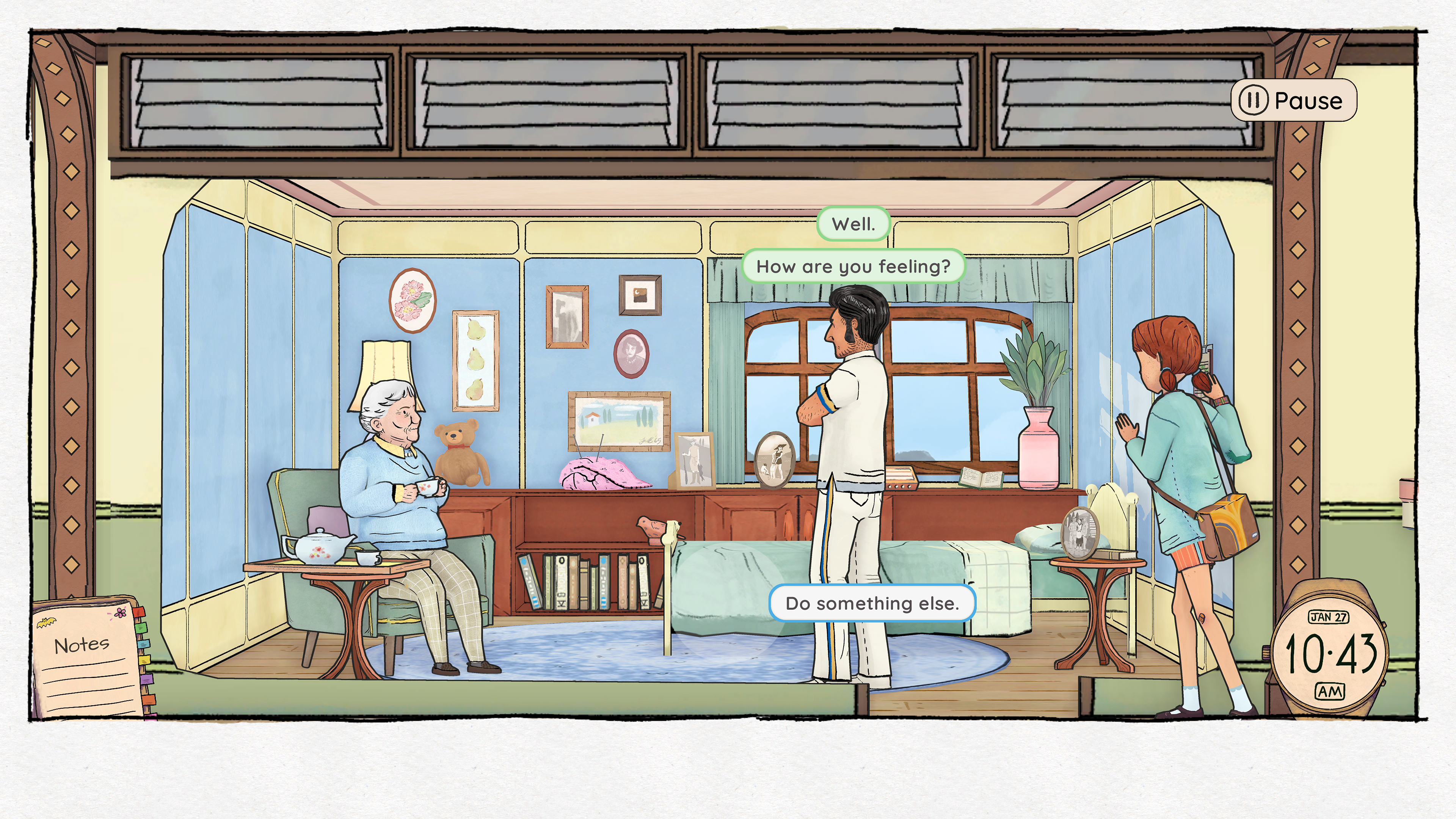

It is not, admittedly, a fully organic shift in perspective. The airship-related dialogue dries up after a while, but for me, it felt like an accurate reflection of how my own curiosity evolved. Who’s the VIP set to arrive in a few days? Why did that one nurse quit? Who was the patient that died, and how did the others get along with him? I investigated these threads by asking characters outright or hearing details in passing, and in the process, I arrived at a place where I cared most of all to learn from these characters as I spent time among them. . I wanted to know about the slow-speaking Mr. Pruiss and the paintings he’d been gifted by his Austrian family, about the nonverbal Tomi and her bear statue that curiously stands out amongst the plants in her room.

The facts of life

Sometimes, though, the leads don’t pan out, or a character has had enough of your curiosity for the moment. Maybe you’ll come around to that missing piece later, but maybe you won’t and you’ll have to draw your own conclusions. That’s life.

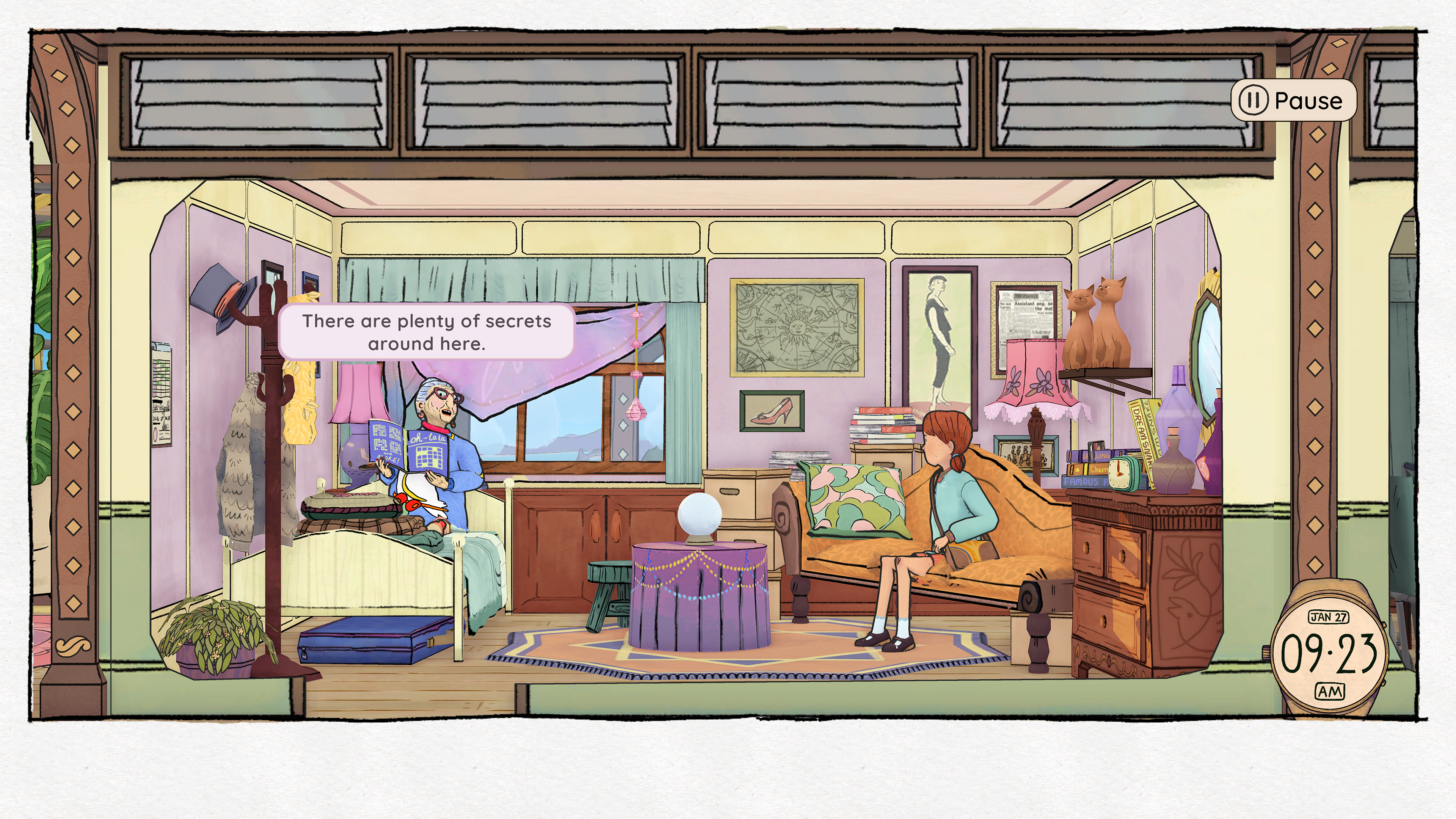

In that regard, the notebook’s organization makes a little more sense. By not highlighting new entries and foregoing any sort of checklist, the details of these lives avoid becoming overt collectibles. You do not 100% the storyline for crotchety astrologer Esther, and when I replayed the game intending to spend more time around her, I was shocked at how much I hadn’t seen, how many distinct actions and how many bespoke animations. On the first playthrough, I found the writer Mr. Avery to be self-important in a bit of a charming, eccentric way. On the second, I found his actions to be rooted in his mortality: he was desperate to pass on his wisdom, worried that the books he’d written were no substitute for raising a child of his own. I heard about an argument he had with the administrator, and I haven’t reached the point of seeing it yet (if it can be seen) on the replay, but I have my suspicions that his advice grew overbearing.

So much of Wayward Strand flies in the face of common game design wisdom, where you need to clearly explain things to the player, emphasize their forward progress, and lead them by the nose to all the good parts. You don’t acquire new powers or unlock new areas on the ward, and you aren’t getting a little pop-up pat on the head beyond the notifications for your notebook entries. During the ride home at the end of each day, the elder Ms. Beaumaris even squabbles with you over your actions.

She’d be short with me and say that I wasn’t helping out nearly as much as I ought to. As far as I can tell, this conflict happens no matter what you do. It’s a preprogrammed argument in the literal sense, but also reminiscent of those conflicts you have with your own relatives, where it feels as though they’ve latched onto an excuse to extol the grievances that have been simmering in their brains.

You certainly wouldn’t know it at a glance, but the game’s writing made me think of Pathologic 2—when I interviewed that game’s narrative designer, she told me it was “designed around an incomplete playthrough. The idea is for the player to fail, miss quests, and overall play suboptimally.” So, too, is Wayward Strand; on my first playthrough, I spread my attention liberally throughout the ward, and in doing so I missed the depths to characters like Esther and Mr. Avery.

Behind the storybook art style and the gentle music, this is another game intent on giving the sense that life goes on without you. In the time it takes you to travel from one part of the ward to another, something might have happened that you didn’t quite catch. Where Pathologic 2 accomplishes this through factors like map size, Wayward Strand does it by having you wait for animations to complete. Casey will take her time sitting down in a chair, pressing an elevator button, or climbing the stairs, and that can admittedly take some getting used to.

Once I adjusted, however, I found these animations more or less appropriate for the hands-off style. Where a story-driven first-person game like Adios left me restless for letting me retain movement and camera control throughout its varied workday, Wayward Strand made me less antsy even if it was, on paper, far more languid. I felt comfortable sitting back and watching the drama unfold from its dollhouse-like perspective; some of the actions and dialogue are triggered by simply hanging out in a room and waiting to see whether its resident chooses to engage. Other characters seem nearly impossible to win over at all. They remained obstinate or outright unresponsive to me, and that fact only made the world of Wayward Strand feel more nuanced and complex rather than artificially gated by timers and percentages.

A child’s eye view

When I worked at a library, you’d see piles of “cozy” books go out among adults, droves of chaste romances or pun-based mysteries where acts of murder are purely incidental to some twee detective work. Their selling point is that they’ve had the darker, challenging undercurrents shaved away.

And then I’d see children’s books, which could be shockingly varied and adventurous. Material that you’d assume was made exclusively to shield and shelter was instead designed to educate from a viewpoint the target audience could understand. It’s what happens when you allow an industry to decouple itself ever so slightly from the exclusive pursuit of profit; I can’t imagine them being huge sellers, but someone decided they’d be valuable all the same.

Likewise, I don’t know how commercial Wayward Strand is. It seems defiantly uncommercial or perhaps even a terrible idea where profit margins are concerned, so I’m not surprised to see it sold as a “cozy” sort of game; it featured in the first Wholesome Direct. But “cozy” and “wholesome” belie the nuance and the depths of emotion here, the pain and stress and fear beneath a crayon exterior.

In that sense, the use of a child protagonist here is perfect. Though the characters are often happy to talk, there are other times when you can feel yourself being discounted, being treated like wallpaper, or being regarded as a nuisance. As Casey, we often feel powerless, with events proceeding no matter what protests we’ve made. The troubles of the ward remain visible, sometimes having taxed its workers and residents to the point where they can’t be bothered to put up the front for talking to kids. They gossip and they argue, lashing out due to stress and sickness.

Don’t get me wrong: this is less a children’s game than one broadly appropriate for them, if they watch someone else play it or if they have the patience to do so themselves. But like a children’s book, Wayward Strand is written to talk to an audience in terms they relate to. It is warm and uplifting and heartfelt in the ways we often seek out as an alternative to our own world, but it also resists the medium’s tendency to hammer lives into a tidy stream of events that feel fair and make sense. Wayward Strand deserves to be lauded for any number of reasons, but chief among them is how clear-eyed it remains about the complexities and the hardships of being alive.